Sarah Mitchell died quietly on September 10, 1946. You will not know her nor, at the time, would you have noted her absence. Her ordered, deeply religious life on the east coast of Tasmania was unremarkable – except for the extraordinary diligence which saw her, from age 13 until her death at 93, record her life.

Sarah Elizabeth Emma Mitchell (1853-1946) closely observed her daily life, and wrote about it every day. Her’s was a life captured through words – a melange of prosaic comments about the weather, visitors, the garden, the family dog or an outing to the beach with sister and friends. Yet, upon gently opening the covers and turning the pages of her more than 80 works, what begins to emerge is a woman who valued herself and felt deeply rooted in her family and her colonial coastal life.

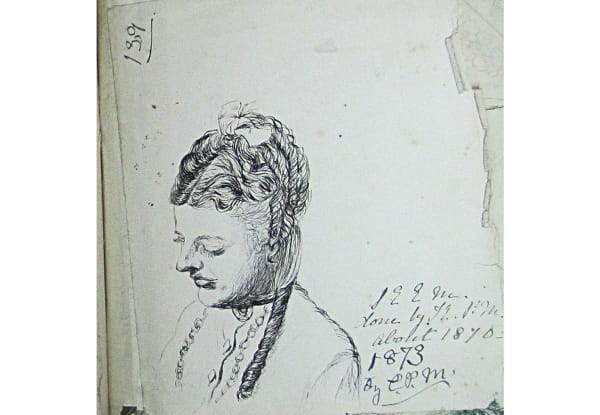

The captivating text, most of it penned more than 100 years ago, slowly presents Sarah to us. We are drawn into her life, her seeming simple world embedded in Victorian mores. We discover a life lived with structure and executed with self-confidence. An unspoken but palpable strength is ever present. From 1866 to 1946 diaries, letters, visitor lists and appointment books were penned and filled, often to overflowing, with words. Sarah compiled large, handsome handmade scrapbooks and a sketchbook replete with tender illustrations by her sister Catherine, Catherine’s 1877 wedding bouquet and, a year later, locks of her hair upon her death.

Her life emerges through words.

Thursday April 7, 1870, reads, “Fine. Papa rode Dot twice to Mayfield. Kate, Amy, and I rode Brownie, Fairy & Garry to Swansea, had our photographs taken on horse-back; went to Redbanks to dinner.”

Tuesday March 17, 1891, “15 points measured by rain gauge. Fine NE breeze. Mother out a little. I read about three hours aloud to her afternoon. Made cakes morning.”

The diaries are observations of 19th and early 20th century life, but also transmit a deep aesthetic and visual quality. The words, thoughtfully crafted, may be viewed as merely a layer to be observed, perhaps not even read or understood. Clearly legible, flowing text is often intersected and overlain by cross-hatched writings. These are strong darkened pieces woven with hidden drama. The message, now almost illegible, sees layers of words and ink built up at right angles to the first set of messages, drowning the communication and almost blocking the reader from her world. Here, interdependence of ink and paper guides and defines the layout and words. They boldly constrain the handwritten text. Some day-entries are only partially filled while others explode with row upon row of flowing intermeshed writings, stopping abruptly when the day is done. Paper was expensive and diary books a precious commodity so Sarah, an organised woman, constrained her writings to the space allotted for the day’s entry.

These small personal works are and become Sarah, each an object of devoted self-expression, each are stories shaped by her. Whether viewed as functional art or merely acts of communication to an unknown reader, her diaries have become symbolic representations of an internal life now open to interpretation. They evoke emotions, are beautiful and aesthetically pleasing, but also had a utilitarian purpose. Sarah’s sketchbook and diaries have never been transcribed. Her handwriting takes considerable time to untangle so the fullness of her life remains hidden.

It was a life of Victorian duty. There were 10 children, three dying in infancy and one as a teenager from extreme bullying. But it was her sister Catherine’s tragic death from hydatids that one senses was the event that defined the direction of Sarah’s life. Her father died soon after and, as the only daughter still at home, the next two decades were spent caring for her mother and helping on the farm that was struggling financially. “Dear Kate” died when Sarah was just 25, yet more than 50 years later, in the early 1930s, Sarah gathered all Catherine’s drawings and personal mementos into a large memorial sketchbook – a poignant reminder of what had been lost.

Sarah never married, was devoted to her family and compelled by a deep sense of duty. Throughout her life her words were her constant and ever-present companion. They formed the cornerstone of life’s routine. No one yet knows what lies beneath her expressive, interwoven, inky art, her arrangement of words cast across more than 80 diaries, list books and notebooks. One day they will be transcribed, their contents unpicked and her life revealed.

Clearly proud of her work, perhaps unintended to be read or interpreted by its creator, Sarah gifted her precious sketchbook, scrap and list books, and diaries to The Royal Society of Tasmania during the final years of her life. Her niece donated the rest of her works upon Sarah’s death. They are held in the University of Tasmania Special & Rare Collections Rare Room which holds The Royal Society of Tasmania Library Collection.

Lynn Davies established and curated the University of Tasmania’s Waterworth Optical Collection. She formerly worked at the university as its principal science librarian, special collections manager, curator and researcher for more than two decades. Davies established a social history museum, consulted for local government and worked on numerous heritage projects. She continues to research the Waterworth buildings, their wartime fixtures and the story of their remarkable female workforce.

The Royal Society of Tasmania (established in Van Diemen’s Land in 1843 and the oldest Royal Society outside the UK) Library Collection forms a major part of the University of Tasmania Special & Rare Collections – more than 25,000 collectable and rare books, handwritten manuscripts, diaries, letters, lantern slides, paintings, photographs, academic regalia and early charts, plans and maps. The collection has national significance status. It is open to the public Mondays to Wednesdays.