Two roads lead to the Tasmanian west coast: one from the north and one from the south. It is the route out of Hobart, along the Lyell Highway, which is the more dramatic. Rising gradually to the southern region of the central mountains, western Tasmania begins at about the site of the Derwent Bridge Hotel. Beyond this, the highway leads through sections of buttongrass and rainforest, with mountains of dolerite and quartzite and conglomerate all appearing over the road, often blanketed in a preternatural gloom.

Just above Queenstown, the thick green vegetation suddenly vanishes, leaving exposed the legacy of an industrial past, bare terrain the colour of burnt sienna. It’s been described it as a moonscape, or compared to an arrival on Mars. And then the road convulses into a series of hairpin bends. This descent into Queenstown is unforgettable.

There are people who do not like Queenstown – travellers who like their tourism packaged – but this is one of the most fascinating places in Australia. It’s definitely a book not to be judged by its cover, and certainly not somewhere that can be comprehended in an afternoon, which is the amount of time that many visitors give Queenie, usually on their way to Strahan.

Queenstown, New Zealand, is a high-adrenaline location with a million activities that need to be ticked off. Queenstown, Tasmania, is a place where you need to rent a room and spend a few days walking slowly around its streets, asking questions or eavesdropping. And when it rains, which it will, sit inside at a window and watch these streets drip, and let your imagination run loose for a little while.

The town itself is a mish-mash of architectural styles and eras. There are a number of gorgeous Federation-era buildings still in operation, such as the old post office, the Paragon Theatre, or the Empire Hotel; they sit not far from squat shacks, rundown cottages and abandoned stores. There is a fairly ugly installation of mining equipment at the northern end of the town. Further south, along the railway tracks, is an unofficial statue, a tree built out of cans of Boags Draught, the cans having faded to a uniform bluish hue after some time standing in variable weather.

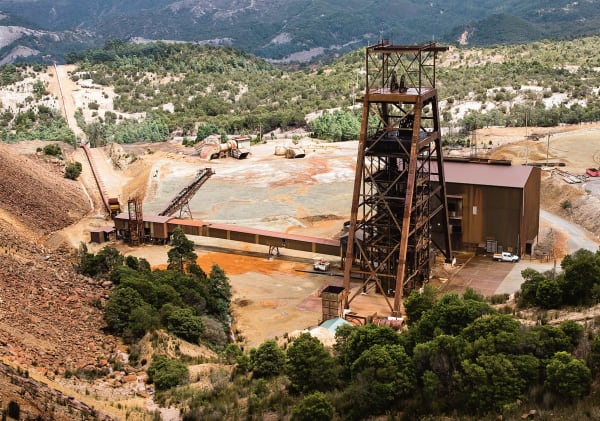

It is true that the hills of Queenstown are almost devoid of vegetation, and not because of some natural occurrence, but because of environmental destruction. This was a mining town, home to one of the largest copper mining operations in the world. The mineral wealth of Mount Lyell was discovered by a prospecting party in 1884. For some decades, Tasmania had been clamouring for a gold rush, but whilst a little gold was found here, it was the lode of copper at ‘the Iron Blow’ which proved to be of greater value.

The government’s first geological surveyor had come through here with his party of explorers in the 1860s, but hadn’t thought much of it. It’s hard to see how he missed the mineral potential, in what eventually proved to be Tasmania’s richest valley. This was Charles Gould, the son of famous British naturalists, and a brilliant geologist in his own right. Some say he was somewhat uninterested in being a glorified gold-digger, and this may be the case; he made a range of original geological observations, proving his ability, if not his aptitude for this particular task.

Gould also named the six major mountains in the area of Queenstown, all for contemporary scientists. Aside from Lyell, we have Darwin, Owen, Huxley, Jukes and Sedgwick. The nomenclature commemorated the great scientific debate of the day, on the theme of natural selection; Gould diplomatically honoured three scientists from each side of the argument.

Charles Gould also named the valley ‘Chamouni’ (a corruption of Chamonix), which perhaps was a bit fanciful to stick. It became the Linda Valley, and when the surveyors passed through here, he was struck with the stereotypical scenario of a forested western landscape: a network of gullies choked with plant life, in which ‘there was no open land visible’. By the time the Mount Lyell Mining Co. roared to life at the beginning of the 1900s, the plants were beginning to wither, die, and disappear entirely.

This was thanks to the mine’s smelting activity, the brainchild of Robert Sticht, an American-born engineer who produced pyritic smelting furnaces that both efficiently cooked down the copper and also spewed out terrible sulphurous fumes. Meanwhile a handful of towns had grown around the mineral-rich mountain, and two railways ran out towards the west coast – it would be decades before it became practicable to transport either people or goods by land, until the original Lyell Highway was finally established.

Widely respected in the mining town, Robert and Marion Sticht lived in a cottage of pink sandstone called Penghana, which now operates as a bed and breakfast. Here, the Stichts had an impressive book collection and art collection – it is pleasing to think of works by Dürer and Rembrandt in Queenstown. Robert played the zither, and Marion was a leading figure of a pioneering women’s society. (A novel by Tasmanian author Brett Martin, Marion, is recommended reading for a trip to Queenstown.)

A lengthy visit to the Galley Museum is an excellent way to take in the early history of Queenstown and the west coast. The Galley is more eclectic than sophisticated, exhibits contextualised with a colourful and often lengthy description. Photographs, folk poetry, pub anecdotes and personal reminiscence all combine to make for a great tour of this region’s tremendous past.

For more history, Queenstown Heritage Tours runs a trip to Lake Margaret, a hydroelectric power station above the town which was built between 1912 and 1914 by the Mount Lyell Company. The hydro station contains original machinery and infrastructure including a pipeline, made of king billy staves, more than two kilometres long and still operational.

The same company runs tours to sawmills and abandoned mines, as well as trips up Mount Owen and into the Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers National Park. Another tour company, King River Rafting, leads paddling trips from Queenstown. Huon pines fringe the river and the craggy mountains of the West Coast Range loom overhead. Wedge-tailed eagles and sea-eagles frequent the area, and so too do platypus and freshwater crayfish.

If you don’t want to submit yourself entirely to the water, you can still head to the King River. One of the short walks cut by locals into the forests south of the town, a 40-minute stroll through vivid green, will take you to the confluence of the King and Queen rivers. This is one of the most evocative sites in the west. Here, the fresh dark currents of the King River meet the poisoned Queen River, which is so polluted from historical mining activity that ecologists suggest it will take a millennium to recover.

The landscape offers up all sorts of similar contrasts. Much of its energy comes from this, and it is at least partly the reason esteemed artist Raymond Arnold moved to Queenstown a decade ago, establishing his LARQ gallery here. Whilst it is now not officially open, the artist remains, and his influence on the town is clear. A painter and printmaker, Arnold is especially attuned to the contours and textures of the ‘elsewhere world’ that is western Tasmania, and depicts it faithfully.

The old bank, another Federation beauty, has been refurbished and turned into a contemporary art gallery, inviting artists in residence as LARQ had previously done.

The rail rakes are from old ore carrying carriages that once operated at the Mt Lyell mine.

For avid walkers, the many mountains around here will be alluring, but even those who haven’t packed their bushwalking boots might find it worthwhile to wander up to a vantage point above the town. You’ll need to ask a local how to pronounce it properly, but the rounded hilltop of Spion Kop is not far from the centre of Queenstown and offers a fine perspective of this fascinating place. With some knowledge of the area’s history – and Geoffrey Blainey’s Peaks of Lyell is as good as anything for this – it is easy to imagine scenes from the past.

It’s also the best view of an infamous local landmark, Queenstown Oval. While some trees have begun to recolonise the hillsides, the footy ground, known as the ‘gravel graveyard’, remains barren. I can assert this from personal experience, having played on it not so long ago. At the beginning of the match, there may have been a few sprouts of grass emerging from the loose sandy gravel, but after a couple of hours of heavy rain, and forty-four pairs of boots hoofing it up and down the field, none remained. It really is gravel. My knees still wear the scars of that day.

This football match was the unlikely finale of Queenstown’s arts biennale, known as The Unconformity Festival. I say unlikely, but how else should an arts festival in Queenstown finish? The Unconformity is one of the country’s most original festivals, utterly absorbing the history and environment of a place and presenting it in various artistic media, devised by creators from around the world. For me, it is unmissable, a festival that is both a genuine community event and a legitimate experience of contemporary art.

This article provides a glimpse into Forty South Publishing's latest project, Volume II of Towns of Tasmania. Storyteller Bert Spinks has sharpened his quills and Pen Tayler is crawling out of bed at shockingly early hours to find the dawn light and winter mists through which she so likes to photograph Tasmania. While the second volume is on its way, find a copy of the first Towns of Tasmania: A Journey Through Time via the Forty South online bookshop.