Photographs from the Theatre Royal Collection and the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

Sound is cardinal in theatre. Whether it’s a speech, music for dance, the murmuring of an audience or the enthusiasm of its clapping, or the thunder of sudden, complete silence, sound is an essential part of a performance experience.

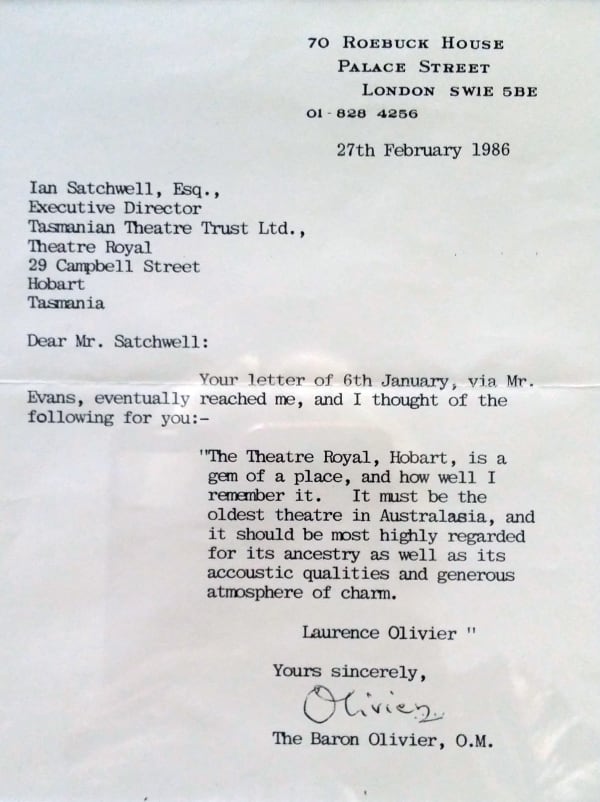

When Friends of the Theatre Royal (FOTR) tour guides lead groups into a small, disused dressing room near the back of this historic building in Hobart, the visitors never fail to be enthralled by the sound of Sir Laurence Olivier’s voice urging an audience to preserve the unique space the theatre represents.

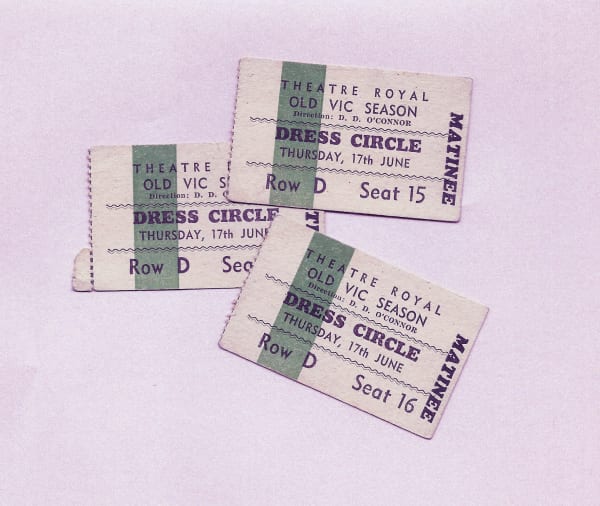

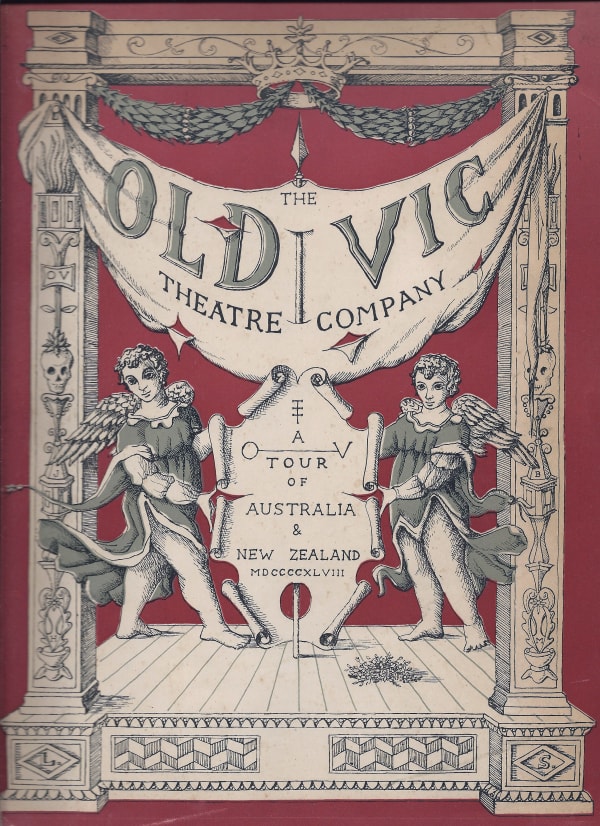

Olivier toured Australia with the Old Vic Company in 1948 – a time when the Theatre Royal was threatened with closure – playing the comedy School for Scandal with his wife Vivien Leigh. The pair were photographed in that tiny dressing room and you can clearly see its oak leaf wallpaper behind them. On the opening night of the Old Vic’s sold-out Hobart season, Olivier stepped to the front of the stage, deemed the Theatre Royal “a beautiful little theatre”, and reminded patrons that their parents and grandparents had sat there as audience.

Olivier’s voice has been described as having a “whiplash clarity”, but it is the warmth and familiarity in both his words and his tone that draws positive responses from visitors as he talks of the importance of the theatre and mentions ABC journalists hovering around him like guardian angels. Today the old, uneven floor, the plaster that covers the bricks and the crumbling sandstone on one of its walls give an extra resonance to the voice of the dressing room’s former occupants.

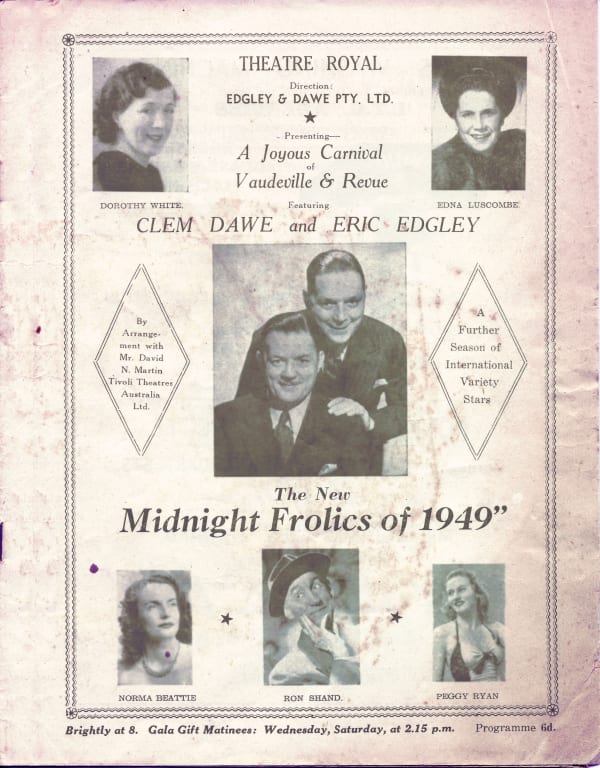

The voices of performers who played on the Theatre Royal stage after Olivier’s visit, as well as those who remember these shows, tell other compelling stories about the theatre and the enormous variety of live shows presented there. For instance, Tim Munro, present CEO of the Theatre Royal, has fond recollections of Dorothy (Dot) White. She was originally a young member of the family that formed a company called Edgley and Dawe that staged performances of the Follies which elevated audience attendances in the 1940s.

One show Dot performed in, The Midnight Frolics, was promoted as “good clean wholesome entertainment”. She appeared with other members of her family as actress, singer, dancer and anything else required of her on stage. The program usually featured popular and classical music and one-act plays, with the addition of dancers, comedians, acrobats and lecturing celebrities – all on a single bill. Michael Edgley, a son of the founding partner, continued his father’s entrepreneurial pursuits to head one of Australia’s most successful theatre and concert promotions businesses.

Tim Munro tells me that his great aunt, Dorothy Reynolds, was a close friend of Dot White. The openly gay pair rode motorcycles and ran a speakeasy/café called The Chalet at Austins Ferry in the 1960s and ‘70s. The building still stands and Munro remembers his aunt, whom they called Doff, as down-to-earth and chain smoking, while Dot White (known as Dossik or Doss, after her earlier marriage to a Russian violinist), had the manners of a refined English lady, “all feminine and Earl Grey tea”, says Munro.

Visits to the pair were a highlight of his childhood.

. . .

Television and radio presenter Ken Short was associated with the Theatre Royal from his arrival in Tasmania in 1952. He remembers the first show he saw there – a production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Gondoliers, starring well-known local musical performers Lyall Beven and Mavis Brinkman. In a later performance of Camelot, Short wore imported armour, including footwear, made of fibreglass. He recalls it was painful to walk in, especially up and down steps on stage. Ken describes the armour as eventually becoming “sort of impressed on the top of your foot, a rather sensitive part of one’s body”.

During the 1960s, the Theatre Royal Light Opera Company performed shows such as The Gypsy Baron, Orpheus in the Underworld and The Mikado. Together with the Youth Theatre, Gilbert and Sullivan Society, Tasmanian Opera Company and dance and other drama companies, local and mainland performers became household names and the many shows they appeared in eagerly anticipated. Ken Short recalls Elizabeth Whitehouse playing Yum Yum in The Mikado and continuing to build a stunning career that has included playing in Fidelio and Rosenkavalier at La Scala, Milan.

In The Gypsy Baron, Short played the part of the village mayor, a pig farmer. He says his dialogue was interposed with porky-type comments like, “Take me as I ham,” and punctuated with pig noises. He devised his own piggy make-up, including a snout that drew appreciation from Diane Large, the director. He also played the piano in several performances, from a hospital review called Bugs Bungle to Jerome Kern’s Showboat.

Short is full of amusing and informative stories about the theatre, with insights into local personalities, as well as details about big names in the Australian and international musical world who performed there.

Critic Wal Eastman and his wife Berenice were impressed with the scope of shows presented at the Theatre Royal following their arrival in Tasmania in 1973. They remember Tom Stoppard plays, Peter Pan, Oscar Wilde works, The Rocky Horror Show, Don McLean and the Sydney Dance Company, members of which Berenice invited to their Hobart home for midnight supper after a performance, and the company then came regularly for several years.

The Eastman children grew up with shows and performers a regular part of their lives and sustained associations with theatre into adulthood, as did many families involved in the Theatre Royal. Berenice Eastman tells the story of Barry Humphries, who had a conversation with her children while he was on stage – they had somehow ended up sitting in the Royal box, which he referred to as “the ashtray”.

Wal Eastman’s reviews were a regular feature in the Mercury. He describes filing copy from a phone at 1am after the first night of a performance. It was transcribed immediately, appearing in that day’s newspaper. His reviews are remembered for their fairness and compassion; Berenice says he saw the potential of performances and always tried to give encouragement to members of a production.

. . .

The theatre flourished in the 1950s and early ‘60s, largely due to the establishment of the Tasmanian branch of the National Theatre and Fine Arts Society (NATFAS) under the presidency of Bruce Piggott. The society encouraged serious opera and ballet with the enthusiastic assistance of post-war migrants such as Walter Stiasny, Stefan Haag and Mischa Slavensky, the latter a former dancer with the Borovansky Ballet. One of the aims set forth at the NATFAS formation in 1949 included eventually extending the Theatre Royal building to include a dramatic academy and music conservatorium on land next door owned by the Hobart City Council. This is now being achieved in partnership with the University of Tasmania and the State and Federal Governments.

During this time, NATFAS worked with the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust on 20 weeks of joint productions per year, hosted many significant events such as the Australian premier of Wolf Ferrier’s School for Father’s, while the Theatre Royal Workshop Studio provided training in dramatic art, sought out talent and coached members for roles in future productions. ABC concerts also played there and conductor Walter Susskind described the Theatre Royal as the only establishment of its kind in Australia that had the atmosphere of a classical theatre.

Strong ties that reinforced the growth of the performing arts scene in Tasmania were developed between local and mainland theatre companies, writers and performers. For example, Melbourne musical and theatrical entrepreneur Hector Crawford would often fill a vacancy in the orchestra with one of the musicians on his books. Sydney writer and political commentator Bob Ellis, and then Tasmanian resident Michael Boddy, collaborated on The Legend of King O’Malley. Ellis believes this musical play revitalised Australian theatre when it toured Australia in 1970.

The theatre was also a social and educational venue – school plays, university revues and eisteddfods are well remembered by Hobart residents.

. . .

While written histories and documentation are essential to preserving the past, however, it is oral history that gives detail and significance to events. As the Theatre Royal enters a new phase in its history, which will see the small building become part of the larger Academy of Creative Industries and Performing Arts, an Oral History Project implemented by the Friends of the Theatre Royal will record and make available personal stories and observations from the theatre during the years 1948-84. Friends of the Theatre invites readers who performed there, assisted in productions, were employed in an administrative or technical capacity, or visited as patrons to contact them if they would like to offer their memories in interviews that will then be recorded for posterity.

Critic Leo Schofield alludes to the Theatre Royal’s “sublime acoustics – as flattering as candlelight to the human voice’’. With such recordings of theatrical voices the theatre’s past comes alive again for a short time … in sound. The Oral History Project will acknowledge the diverse range of personalities who contributed to the development of a strong theatrical and vibrant arts culture in Tasmania, while the Theatre Royal continues to provide present and future generations with memorable experiences.

This article was first published in issue 80 of Forty South magazine.

Carol Freeman is researcher and writer who has lived in Hobart for over 30 years. Her work usually centres on human-animal studies but since moving to Wapping, where the Theatre Royal is situated, she has become fascinated by the history of the area and has rekindled an interest in drama and the performing arts.

Her work appears in books and academic journals, exhibition catalogues and art magazines on topics that connect art, science and history in innovative and provocative ways. These include a co-edited book Considering Animals: Contemporary Studies in Human-Animal Relations, essays such as Is this Picture Worth a Thousand Words? in Australian Zoologist, catalogue essay Reconstructing the Animal for an exhibition at Tasmanian College of the Arts and book reviews for Historical Records of Australian Science. Her major publication, the book Paper Tiger: How Pictures Shaped the Thylacine, is published by Forty South. Since 2015 she has been a regular contributor to Forty South on a variety of subjects.