Jimmy Wright was 18 years and five days old on Sunday, October 1, 1967, when he woke up in his hotel room in Burnie and realised he’d missed the train.

Jimmy Wright was 18 years and five days old on Sunday, October 1, 1967, when he woke up in his hotel room in Burnie and realised he’d missed the train.

The train was carrying his North Hobart Football Club teammates back to the capital. The day before, Jimmy had played in the State Australian football grand final, a game that would soon be declared both a legend and a no game. The reason for both was a crowd invasion of the playing ground and removal of the goalposts to prevent North Hobart’s full-forward, Dickie Collins, from taking a kick to win the game.

The match was described by Tasmanian academic, writer and football tragic Pete Hay – who was there – as “emblematic of a wonderfully tribal football that was passing”.

There are many aspects of the game – apart from the removal of the goalposts – that are very different from football today. Let me explain.

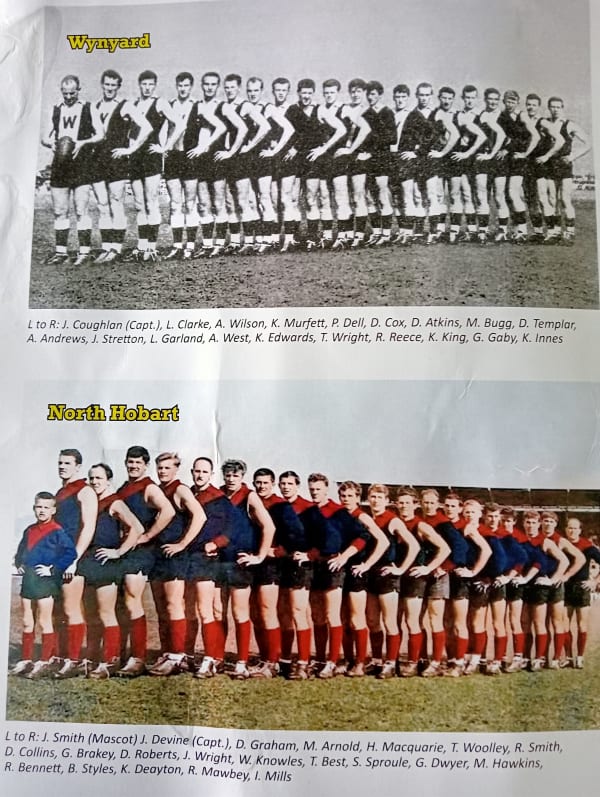

The way football worked in those far-off days was that there was a southern league called, rather arrogantly, the Tasmanian Football League; a northern competition called the Northern Tasmanian Football Association; and the coast, the North West Football Union. They all had their seasons, and then three premier clubs of the various competitions played off to decide a state champion. In 1967 the state grand final was to be between Wynyard of the NWFU and North Hobart of the TFL.

Wynyard had had a dream year under their captain-coach, John Coghlan, losing only one game all season. North, by contrast had had a slow start to the season and finished in fourth place before winning three finals to become TFL premier. Then in their fourth final in four weeks, they beat East Launceston to earn the right to travel to Burnie and play Wynyard for the state title.

North Hobart was captained and coached by John Devine, an ex-Geelong player. Coghlan came from Oakleigh in the old VFA. It was a common practice in Tasmanian football for elite players nearing the end of their careers to be hired from Victoria as a captain-coach. And in Coghlan and Devine, the system really worked.

One thing that really stands out as different to today is the age of the players: Eight of the Wynyard players were under 20 and 14 under 22. And careers weren’t, on the whole, long.

My friend, Jim Wright, although starting first grade football at 17, retired by the age of 24 despite playing for Geelong in the VFL and in the VFA, and returning to Tasmania to captain North Hobart to a premiership under Devine as coach. Players over 30, like the two playing coaches, were a rarity.

But they could provide a calming influence.

One day Jimmy was playing on Stu Spencer, the captain-coach of Clarence, and the epitome of the over-30 captain-coach, when a brawl broke at the other end. Jimmy started off to help his teammates, only to be restrained by Spencer, who grabbed his jumper and said, “Don’t be stupid, son.” Spencer, at 36, was twice Jimmy’s age.

The North Hobart players travelled to Burnie on the Tasman Limited, the last passenger train in Tasmania, and not long for the chop. There were delays and the journey took nine hours, the team arriving at 9.15pm on the night before the game. However, some players had put together a substantial betting stake, and went to a pub to put a big wager on their winning – reportedly the then-enormous sum of $3,000. Again, a huge difference to today, where sport betting is legal and promoted. I imagine the players had to find an SP (starting price: off-course and illegal) bookie to take their bet. These were not uncommon. My barber when I was at Launceston Grammar in the 1960s was an SP bookie. Grammar was near Mowbray Racecourse.

The next day, the game got started with a gale blowing off Bass Strait, hugely favouring one end. Devine of North won the toss, kicked with the wind and North turned at quarter time 19 points in front after inaccurate kicking for goal. Wynyard made them pay in the second quarter and led by 20 points at half-time.

What is striking about the match, compared to the modern game, is the violence. Early in the game, Coghlan and Devine went head to head in an epic clash, in which, for once in his career, the hard man Coghlan came off worst. He was apparently knocked out for a second or two – but there were no concussion rules back then. In another incident, one Wynyard player had to have his eyebrow stitched on the boundary (you couldn’t come off, and there was no blood rule), another had his cheek-bone broken, and three players received serious trainers’ treatment in the last quarter, which is described as descending into violence.

There was also a full-on brawl – not uncommon in those days. Alison Alexander, who wrote the history of the Clarence Football Club, said that one of her correspondents reported that if the game was going badly, they would “throw all the cards in the air and start a brawl” in the hope of changing the momentum.

Different times indeed.

With the wind, North got back on top in the third quarter, largely – as players of both sides agree – through the Herculean efforts of John Devine, the North Hobart captain coach. And they got back to even in the last. Wynyard was one point in front when Devine got a free kick 30 metres out. In the teeth of the gale he didn’t make the goal, but the kick was marked by the North full-forward, David “Dickie” Collins.

And the siren blew. Or, according to the Wynyard supporters, it had blown before Collins marked the ball.

There had been dissent to the central umpire’s rulings (in another difference to today there was only one central umpire) all day by the Wynyard players and supporters, and they had been gathering on the bike track surrounding the oval, in anticipation of a famous win for a small town against a city club. When Collins marked the ball, they invaded the ground and stopped the play. There were many violent incidents, some, perhaps fuelled by alcohol, and some North players were attacked. One was stabbed in the buttock by a woman with a hat-pin! Another was hit on the head by a Wynyard trainer with a first aid kit. It really was a melee, and quite shameful. A senior policeman, even, is reported to have behaved badly.

Dickie Collins shoved the ball up his jumper – he still has it – but he never got to take his kick, because the crowd realised that the goalposts were in sockets and could be removed, so they did. In the face of the raging mob – it really was a dangerous moment – the North players retreated to their rooms where Devine kept them cloistered for half an hour, till they and the mob outside cooled down.

It could have got very ugly.

They then went back to their hotel and, in the parlance of the time, “got on the sauce”.

Sometime during the night, one of the behind posts – the property of the Burnie City Council – found its way onto the train and was laid reverently in the aisle. But the theft of the goalpost had been noticed by the Burnie groundkeeper, and when the North players arrived at the train, the police were there, saying that the train wasn’t leaving till the post was removed, which proved difficult, and eventually effected through a window. The train left, and because of the delay, my mate, Jimmy, who had slept in, managed to catch it up at Penguin with the help of a Burnie taxi driver.

The team arrived to applauding crowds in Hobart.

. . .

Here is a huge difference between then and now which I want to point out, and it ties in with Pete Hay’s point about old-fashioned tribal footy – which wasn’t about money, but about passion. My friend got paid $8 for a win and $4 for a loss. He made $168 for the year from footy. The next year, on the basic wage, I was earning $42 a week slashing grass for the Hobart City Council, so my friend’s $168 for a season requiring two nights a week training, plus gym work and a Saturday afternoon of “vigorous” conflict doesn’t seem much.

So you really had to love your footy to play first-grade in Tasmania in those days given the low pay and the high chance of concussion. Now, of course, we have rules – and a lot of discussion – about concussion, and football is an enormous business, with players paid fabulous sums. Again there’s another difference: boots today are like ballet slippers compared to the 1960s, when they were more like army boots with stops nailed on.

Author's note: I must acknowledge Mick Hawkins’ research into the 1967 match (he played in it for North, like Jimmy Wright, as a teenager), and the thoughts of Pete Hay, Mick Hawkins and Jimmy Wright.

James Parker is a Tasmanian historian (but with deep connections to Sydney), who writes and talks on mainly colonial subjects – especially convicts, women and the Tasmanian Aboriginal people.