The Van Diemen History Prize 2021

Sex, violence and mutiny aboard the Cape Packet

Joint winning story

Saturday, October 1, 1825, dawned bleak and blustery in the port of Cowes on the Isle of Wight. Two weeks earlier, Captain William Kellie, of the Cape Packet, had loaded his cargo at the London docks. Contrary winds made it hard going and it took Kellie 11 days to sail 220 miles to Cowes. Here, he picked up livestock and passengers.

Most had already boarded when one gentleman claimed his wife was too ill to embark. But time and tide wait for no man – or his wife. This morning, the tide was right, and the wind had veered a point in Kellie’s favour. He ordered his first mate, William Ruxton, to weigh anchor and make sail.

As the ship rounded the point and passed Hurst Castle, the three tall rock stacks of the Needles came into view. But not for long. The ship now met the full force of the wind, heavy seas and sheets of torrential rain. In Kellie’s haste, many items of cargo, as well as live animals, were yet to be stowed. Boxes slewed across the streaming decks and two frightened pigs were washed overboard. While the crew scrambled to make things fast, the drenched, seasick passengers retreated below.

All day, Kellie tacked back and forth, making little headway while the gale increased. Begrudgingly, he turned back to Cowes, coming to anchor at midnight. One of the passengers, Henry Hellyer, wrote, “It was mortifying to find we had endured all this and might as well have remained quietly at Cowes”. But there was a silver lining. With an extra day’s grace, the gentleman’s wife recovered sufficiently to board. Another 11 days passed, including a further failed attempt to depart, before finally, on Wednesday, October 12, the Cape Packet embarked on her long voyage to Van Diemen’s Land.

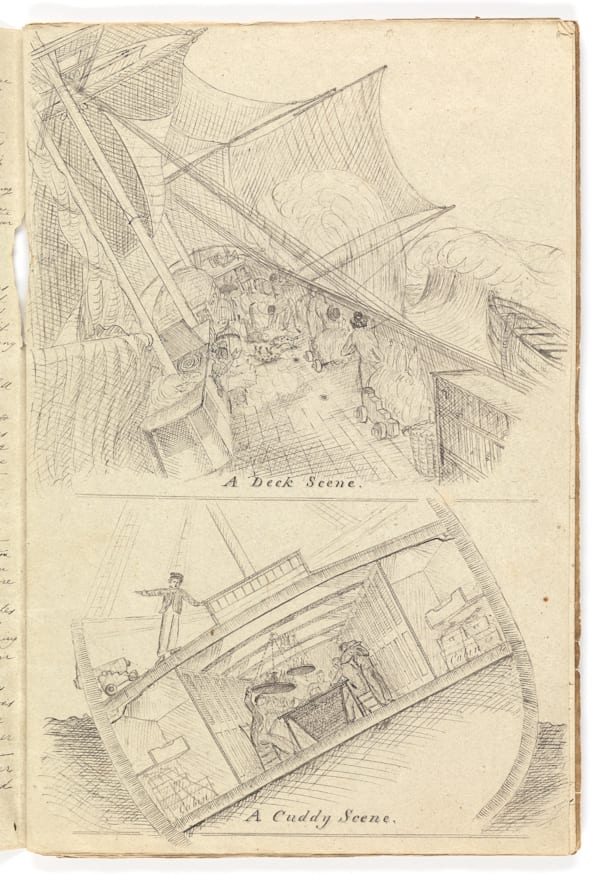

“A Deck Scene” depicts the ship battling the gale in the English Channel on 1 October 1825

The “two frightened pigs” washed overboard are shown tumbling across the deck

“A Cuddy Scene” shows the passengers in the cuddy – an enclosed space under the fore part of the poop (rear) deck which was used as the dining room for the ship’s officers and passengers

from Voyage to Van Diemen’s Land, reproduced with the permission of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office

. . .

The Cape Packet was a 250-ton brig. Her crew consisted of the captain, his two mates and 20 seamen. She may have been small, barely 100 feet long and 25 feet wide, but what she lacked in size, she made up for in speed and manoeuvrability. And she had teeth. On her deck were four twelve-pounders and below was an armoury packed with small arms and cutlasses. The threat of piracy was real, and she would have made a stunning prize. The Cape Packet was conveying valuable commodities to the Australian colonies, including 100 hogsheads of beer, two brewing coppers, iron bar, sheet lead, mill stones and canvas.

But that’s not all. She also carried treasure: 20 boxes of Spanish dollars, worth £20,000 then and millions today. This was the capital with which Hellyer’s employers, the Van Diemen’s Land Company, would establish the first white settlement in north-west Tasmania, the remotest corner of the remotest colony in the British Empire.

Also aboard were 17 passengers, composed of VDL Co “officers”, their families and servants. Their leader was Edward Curr Esquire, the company’s local agent. Curr was accompanied by his wife Elizabeth (née Micklethwaite) and their three boys, Edward, William and Richard, all under the age of five.

Curr’s second-in-command was Stephen Adey, the company’s superintendent of lands. With him was his bride Lucy (née Rede). They had been married just two months. Also travelling with the Adeys was Lucy’s widowed sister, Mary Grimstone. It is unlikely Lucy would have agreed to travel halfway around the world without her older sister. It was Lucy’s ill health that had caused the Adeys to miss that first aborted departure, a fact neither Lucy nor Mary mentioned in their farewell letters posted from Cowes, lest it cause even further distress for their mother.

The other company officers were Alexander Goldie – agriculturalist, Henry Hellyer – chief surveyor and architect; and two junior surveyors, Clement Lorymer and Joseph Fossey. The remaining five passengers were servants, including two young women – maids of the senior officers’ wives.

Due to inclement weather, the passengers spent their first days at sea in the ship’s cuddy, which served as both dining and drawing room. The ship’s galley and the cuddy’s wine bin were well-stocked, and Captain Kellie appeared both charming and thoughtful, telling the ladies they may “send to the steward at any time for whatever we thought proper”.

While the gentlemen smoked, the ladies played chess. Conversation was lively and good-natured. Hellyer found a kindred spirit in Mary Grimstone. They discussed their shared love of art, literature and theatre. Mary was a published poet and novelist and Hellyer told her of his dream to publish his journal, in which he would chronicle their Voyage to Van Diemen’s Land.

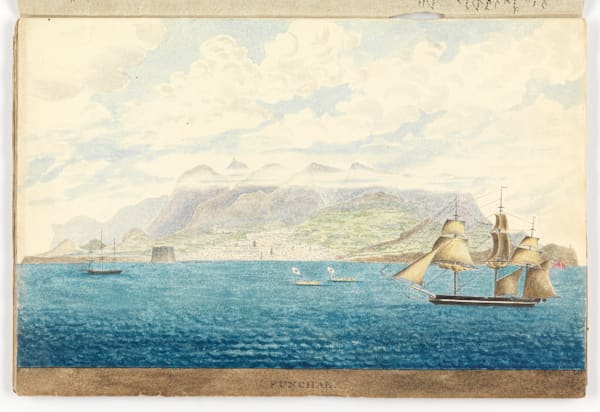

As they made their way south, the weather improved. In less than two weeks, they reached their first port of call, the exotic Portuguese island of Madeira, 400 miles off Morocco. While the ship took on fresh water and provisions, the passengers enjoyed an afternoon ashore. They wandered Funchal’s streets and markets, tasting delicious tropical fruit and sampling the local wines. They “saw no wheeled carriages of any description” on the steep cobbled streets, but instead “sledges drawn by little bullocks about the size of donkies”. Tired but exhilarated, the passengers reboarded and bid a fond adieu to Funchal, as the Cape Packet sailed out of the harbour at sunset.

In the cuddy, oranges and lemons hung from the ceiling. On deck, the ship’s boats were filled with bananas and the stern festooned with slings of grapes, which “made the ship look like a fruiterer’s shop”. With each passing day, more and more time was spent on deck to escape the heat below. On October 27, the wind died, and the ship was becalmed. The sun beat mercilessly upon the white deck, the glare painful to the eye. A canvas awning was rigged up to provide shade.

. . .

The Cape Packet crossed the Tropic of Cancer on October 30. Hellyer noted they had entered the “Torrid Zone”. In the steaming cuddy, sharp words were exchanged over trifling differences. An argument broke out among the servants over the rationing of fresh water. On November 5, Hellyer noted “a deadly silence pervaded the company all the evening … I retired to my oven much vexed to see such disagreements between the captain and our party, particularly as it was about nothing but an angry word”.

Hellyer was mistaken. It was due to more than just “an angry word”. The Adeys’ pretty maid Gwen had caught the eye of Captain Kellie. When she rebuffed his advances, Kellie spread innuendo about her with the crew and rumours among the servants that Gwen was disrespectful towards her employers. Lucy Adey sensed something was amiss and interrogated a tearful Gwen to discover the truth. Stephen Adey was incensed a trusted family servant had been so mistreated and maligned by Kellie.

The Captain was in conference with first mate Ruxton when Adey found him. Kellie was taken aback by Adey’s onslaught. When Ruxton supported Adey, instead of his Captain, an incredulous Kellie dismissed him on the spot, sowing bitter seeds that would be reaped later in the voyage. Backed into a corner, Kellie decided attack was the best form of defence. In a booming voice, so all on deck would hear, he accused Adey of “improper intimacy” with his wife’s maid. Adey “told him he was a liar”. With his honour as a gentleman at stake, there was talk of a duel. A “distressed & agitated” Adey summoned Curr to his cabin. With Lucy at his side, Adey laid the sordid details of the captain’s behaviour before his superior. Lucy later wrote glowingly of Curr’s unstinting support for Adey. From this day forth, Lucy and her sister Mary refused to speak a word to the captain.

In return, Kellie made his passengers as uncomfortable as possible. Whether by design or coincidence, a dreadful stench rose from the bilge and pervaded the ship. The “unwholesome effluvia” left the passengers gagging and their cabin walls streaked with black. Curr demanded something be done. Kellie refused. When Curr pushed the matter, Kellie responded, “I won’t do it and that’s flat.”

Three days later, even Kellie could stand the smell no longer. The ships pumps were inspected and found to be clogged with gravel. It took two days to clear them, then all hands, including Hellyer and the other surveyors, worked the pumps all day in shifts to flush the stinking bilge water from the ship.

Hellyer shows the Cape Packet in the foreground. The two little rowing boats in the centre have raised curved prows of the local “fashion”

from Voyage to Van Diemen’s Land, reproduced with the permission of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office

. . .

Saturday, November 26 began much like any other long hot day aboard the Cape Packet. The gentlemen fished while the ladies sat in the shade of the awning. The Curr boys watched sailors take turns hurling the “grains”, a five-pronged fishing spear with a line at the end, at the large bonito and albacore “sporting and leaping before the Ship’s Bows”. Captain Kellie stood aloof on his quarterdeck. At midday, dinner was served in the “melting hot” cuddy, after which everyone returned on deck.

Later, Curr noticed the captain absent from his usual station. Suspicious, he quietly descended the stairs to the cabins. At the bottom, he found himself face-to-face with a surprised Kellie. Over the captain’s shoulder, Curr saw movement in his own cabin’s doorway. His suspicions were confirmed. Kellie had turned his amorous attentions to Elizabeth Curr’s 19-year old maid, Mary Wogan.

Never one to mince his words, Curr accused the captain of having “seduced” his servant. An indignant Kellie, almost literally caught with his pants down, pushed past Curr, saying he would not be insulted in his own vessel. On the quarterdeck the two angry men stood toe-to-toe. Curr hissed, “I think sir, that ‘tis I that am insulted.”

Kellie ordered Curr from the quarterdeck, and when Curr refused, Kellie threatened to use force. The six-foot, tall broad-shouldered Yorkshireman stared down the captain and replied, “Then you may force me, for I won’t stir.” By this time, all passengers and crew were on deck watching the unfolding drama. The Captain ordered the second mate and two sailors to man-handle Curr off the quarterdeck and barked for his pistols to be loaded and brought to him.

Armed, and once more in sole control of his quarterdeck, Kellie addressed the crew. “My men, there’s a conspiracy on board amongst the passengers. I have been insulted on my quarterdeck. This ship contains specie [coin] and a valuable cargo. What their motive is I do not know. It may be to take the ship and I call upon you all to attend to my orders and report to me every circumstance that comes under your observation – and the first nan who disobeys my orders, I will blow his brains out!”

Mary Grimstone, never one to take a backward step, pushed to the front and regaled the crew, “Take the ship! And make me captain.” Kellie sneered, “A lady’s impertinence is too contemptible to be noticed.” He ordered the passengers locked in their cabins and posted armed sentries. Hellyer’s entry for this extraordinary day finished with the words, “We all wished we had got to Rio, and were determined to proceed no farther than that on this ship.”

Next morning, Curr assembled his officers. He’d regained his composure and resolved to “remain quiet, till we get to Rio”. Captain Kellie, on the other hand, continued to vent his rage. Mary Wogan’s relationship with the Curr family was at an end. Curr told her, “You are going to the gallows as fast as you can”, to which she retorted, “No Sir, I am going to Botany Bay,” – meaning, after they reached Hobart, she would continue with Kellie to Sydney. Mary was no longer Curr’s servant. She’d moved into the Captain’s cabin and was now Kellie’s mistress.34

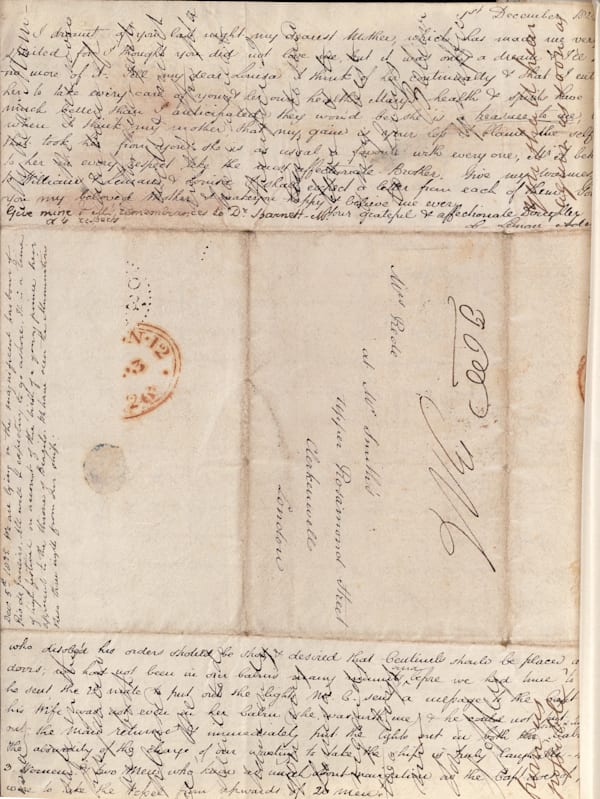

The lights of Rio came into view on the night of December 3. Inexplicably, Hellyer’s journal ends abruptly, mid-page. Curr, aware of Hellyer’s desire to publish the tale of the Cape Packet’s voyage, must have insisted the company’s dirty laundry not be aired this way. But Curr had less power over Lucy Adey and Mary Grimstone. Their letters home from Rio described the scandal in detail.

Then, in a startling about-turn, the passengers agreed to continue onboard the Cape Packet. Lucy Adey wrote this footnote, before sealing her letter.

Dec.r 7th 1825

The Captn Mr Adey & Mr Curr have been before the British Counsel here, & a mutual reconciliation has taken place. The Captn has pledged himself to the Counsel to do all in his power to make us comfortable and we shall sail again on Sunday. I suppose we shall be in V. D. Land early in February. Godbless you all write fully & as soon as possible.36

. . .

Twelve weeks later, the Cape Packet reached Hobart Town. The run across the South Atlantic must have been good, as they didn’t stop to take on water at Cape Town.37

But what happened after the Cape Packet entered the vastness of the Indian Ocean?

According to newspaper reports of the trial of Captain William Kellie, the uneasy truce lasted no more than six weeks.38 On January 24, in the middle of the Indian Ocean, the ship was again becalmed. With the captain in his cabin, perhaps explaining the finer points of celestial navigation to Mary Wogan, Adey and Ruxton decided it would be fine sport to shoot seabirds. With Goldie and two sailors, they lowered a ship’s boat and rowed away from the Cape Packet.

When Kellie heard shots, he burst from his cabin and hurried on deck. He fired a musket and signaled for the boat’s return. When they didn’t respond, Kellie fired several more times. He maintained it was simply to gain their attention, but those in the boat disagreed. When they came alongside, a furious Kellie said, “If they had not returned, he should have fired a carronade into the boat and sunk them.”39 Adey was livid, claiming to have felt the wind of a musket ball.

Three weeks later, Ruxton and the captain clashed violently. The mate was clapped in irons. The mood aboard was black, and the crew’s allegiance split. During the night, someone freed Ruxton by filing through his handcuffs. An enraged Kellie assembled the crew. Again brandishing pistols, he demanded to know who the culprits were. He was met with stony silence. Kellie ordered the ship’s carpenter John Sales to put new irons on Ruxton. When the crew blocked Sale’s way, Kellie warned them, “The first man that interferes, I will blow his brains out.” Seaman Valentine Hobbs spoke up, “Let Mr Ruxton be under a bond, and if he breaks that, do as you will with him.” The Captain’s eyes narrowed, “Out of this, every one of you,” and to the carpenter, “You hold him and I will put them on myself.”

With Ruxton in chains, Kellie went in search of Hobbs, who was in the galley lighting his pipe. Two starkly contrasting versions were presented of what happened next. Hobbs claimed Kellie looked in from the forecastle, got down on one knee, took aim and fired. The ball struck Hobbs’s left side but deflected from a rib and left him with a superficial wound the size of “a crown piece”. Under oath, John Sales gave a different account. He said the captain had only “entreated the men in a mild way” and there was “a great scuffle in the forecastle, and that the pistol, when raised, went off”.

This is the “envelope” which was simply a page of paper wrapped around the other folded pages then sealed. Postage was expensive, so no paper was wasted and the letter was written ‘crossed’ with lines running horizonal and verticle – even on the envelope’s concealed flaps

reproduced with the permission of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

. . .

The week of the Cape Packet’s arrival in Hobart was a busy one for the Magistrates Court. It sat from Monday to Saturday dealing with Kellie, his crew and passengers. Kellie charged the crew with “extreme insubordination, amounting to mutiny”. Hobbs countered, seeking a warrant against Kellie for attempted murder. Then Adey joined the fray. There was much legal argument over whether mutiny even existed as a crime on a merchant vessel (it didn’t) and whether Kellie was accused of capital offences. To Adey’s disgust, his charge against Kellie was dismissed. In the end, only Hobbs’s complaint was pursued. Kellie was committed for trial for “malicious shooting with intent to kill on the high seas”.

A month later in the Supreme Court, Adey, Curr, Lorymer, Fossey and half the crew gave evidence for the prosecution. The defense called John Sales, re-examined Fossey and heard from the defendant. The trial lasted three days, often sitting late into the night. In summing up, Chief Justice Pedder told the jury, “Captains of merchant vessels, like other persons in situations of authority, have certain powers entrusted to them … and might, by reasonable means enforce them.” The jury of six was composed entirely of serving or retired military officers. It took them “only a few minutes” to return a verdict of not guilty.

The whole affair was an embarrassment for the company and its officers, but they did manage to keep the voyage’s more scandalous details quiet. While Adey still bore a grudge, Curr was congratulated by the company directors for having “sacrificed your private feelings to the good of the company”.

Kellie may have been a free man, but no sailor in Hobart would sign on with the clearly “mad, bad and dangerous” Captain Kellie. With half a cargo still to be delivered to Sydney, Kellie swallowed his pride. To placate the crew, a local sailing master, John Laughton, was engaged to command the Cape Packet on the last leg of its journey. Once in Sydney, and paid, Ruxton, Hobbs and the other “mutineers” abandoned ship for good. Kellie retook command, hired new crew and returned to England.

The Cape Packet returned to Australasian waters in 1830, this time fitted out as a whaler – but without Kellie. After his return to England, Kellie seems to have vanished without a trace. It can only be hoped he was never again entrusted with the lives of crew and passengers. The sordid tale of the voyage of the Cape Packet begs the question, how on earth did the Van Diemen’s Land Company directors ever come to enlist the services of a man with such a flawed character and so unfit for command as Captain William Kellie.

Dr Terry Mulhern is a biochemist, university educator and researcher. If he isn’t in his office or somewhere taking a class, look for him in the basement of the University of Melbourne’s Baillieu Library under 994.6 History, Tasmania. He was the 2018 winner of the David White Award for Teaching Excellence, the University of Melbourne’s highest honour for teaching in Health, Science, Agriculture and Veterinary Science. Terry Mulhern was born in north Queensland and has worked at universities in the UK and around Australia, but his heart is in north-west Tasmania.