It was pouring with rain as we toured the abandoned zoo – as if tears were falling from every animal ever confined there.

Now a year later, it’s the centenary of Beaumaris Zoo’s relocation to this sloping hill overlooking Hobart’s River Derwent, where the zoo moved from its original site at Battery Point. Rather than focusing on native animals, the Hobart City Council, which took over the zoo, displayed exotic creatures more likely to draw crowds. It was intended to be a modern zoo of the kind seen in other capital cities.

The wooden picket fence fronting the site is well-maintained and there are remnants of a few enclosures scattered in the long grass. But only Patrick Hall’s two-dimensional sculptures of a sad-looking lion, an elephant and a thylacine on the lower gate pay tribute to the animals that lived and died at the zoo from 1923 to its closure in 1937.

Our guide is Brendan Lennard, former Heritage Officer with the Council. He brings the empty space to life with his words, evoking the calls of animals and the sound of a band, the laughter of children and the kindness of keepers.

Let us take you on the tour.

The lions were the first creatures that visitors saw after entering the turnstiles. The huge lion enclosure with its rocks, painted concrete backdrop and deep moat was the latest alternative to a traditional cage, as it is thought to resemble a species’ natural habitat. However, on at least two occasions, the local fire brigade was called to rescue a lion that had fallen into the moat.

A pair of lions arrived from Sydney’s Taronga Zoo shortly after it opened; a second lioness named Ruby came from Auckland a year later. A cub born in 1926 was called Betty, after the recently born Princess Elizabeth and a competition for possible names for a second cub favoured “Don” for Don Bradman, but the tiny animal was eventually named Sandy. Reared by the zoo curator’s daughter, because the lioness rejected her cub, Betty would rest on her foster-mother’s bed, while Sandy played with the family spaniel and slept among the bamboo canes in the garden of their onsite cottage.

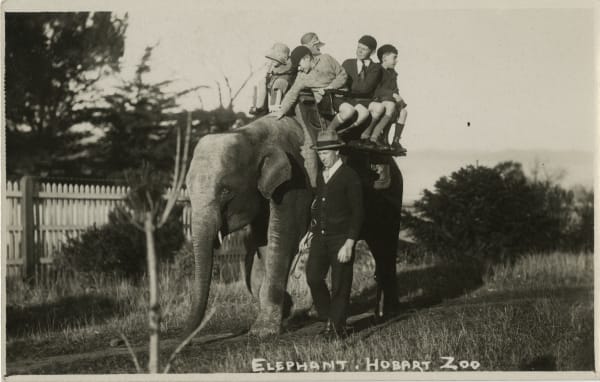

Now we make our way through the long grass to the northern end of the site, where the zoo was extended and an elephant house built, making room for the large animal to walk back and forth to the main entrance giving rides to children and adults. The long-awaited elephant, exchanged for thylacines and wallabies, arrived from Burma via London two years after the opening of the zoo. However Jumbo, as he was called, was pre-adolescent and needed extensive training. After two further years of preparation by his keeper, Albert Brett, and the zoo’s curator, Arthur Reid, he carried his first passengers.

Like so many animals at the Queen’s Domain, Jumbo’s story is heartbreaking. The elephant house was destroyed by fire in 1929, but fortunately the traumatised creature escaped. However, Jumbo proved costly to keep and, although his rides were popular, the council decided to sell him the following year. In October 1930 he sailed to join Jamuna, the female elephant at Auckland Zoo, and was given a new name, Rajah. By then the equivalent of a teenager and needing the firmness and care he received from the humans he knew so well in Hobart, the poor animal became “uncooperative” and was eventually shot. He ended up a museum exhibit at Auckland’s War Memorial Museum.

A month after the opening of Beaumaris Zoo, Sir Henry Jones, the retired managing director of the Tasmanian jam company IXL, promised to procure animals while on an overseas trip. In 1926, with a donation from Jones, two five-year-old zebras arrived from South Africa. The purchase was regarded as a benevolent gesture that other Tasmanians might be inspired to follow.

The zebras, like most acquisitions for the zoo, were a pair. The expectation appears to have been that they would breed, providing a supply of new animals that could be sold or exchanged. They did not breed.

The Mercury newspaper records regular shipments of exotic animals ─ including a sloth, leopards, hyenas and birds ─ from places such as Calcutta and Lahore, often describing their voyages in distressing detail.

After passing the goats, ostriches and emus, we come to the location of the Band Stand. On Sundays, local bands including the IXL Band, Electrolytic Zinc Company Band or visiting military and naval bands, were rostered to give performances. So what kind of music did the animals and visitors hear? In 1923 The Mercury announced that the Hobart Citizen’s Band would play the Adagio from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, songs from Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Gondoliers, the ragtime piece Blushing Rose and Song of Australia.

On the upper side of the hill, we find the thylacine cage. Film footage showing his continual pacing clearly demonstrates how he felt about being confined. This thylacine arrived at the Queens Domain with an injury to his back leg, inflicted by a snare in the Florentine Valley in 1934. His captor, Elias Churchill, wrote, “He was caught by the foot, and I could see he was a nice specimen, so decided to get him for the zoo.” Churchill took him to Tyenna on the back of a pack horse and finally on a train to Hobart.

A woman who visited the zoo in Battery Point when a young girl recalls that the thylacines there “always seemed so tame to me, never were ferocious and always looked sad”. The death of the last captive member of the family Thylacinidae in September, 1936, the year before the zoo closed, was not acknowledged in the press. With the passage of time her demise is a profound reminder of how easily a unique species can disappear.

The white-washed polar bear enclosure, with rocky island, moat and sleeping house, is one of few surviving zoo structures on the site. Two polar bears from Greenland could be observed at very close range, but within a year the height of the island platform was lowered and an extra railing added, as it was feared the huge animals might escape. Though expensive to feed, the bears survived the economic measures imposed upon the zoo in the 1930s and remained there until several months after its closure.

In 1928, the council decided to obtain a pair of Bengal tigers in exchange for some Tasmanian animals. When the tigers arrived from Singapore, two baby Sumatran sun bears accompanied them. Although in poor condition, six weeks later The Mercury reported the bears were “in a splendid state of health, and daily amuse zoo visitors by their quaint and exuberant antics”. For more than a year, these young animals lived in a temporary cage and then in a small, water-logged den from which they escaped by breaking the wire. The male bear was shot after he “buried his teeth” in an attendant’s leg and, when the female escaped and climbed into a tree in the ostrich paddock, she too was shot.

The last cage we come to is where a pair of leopards lived. When twin cubs were born and one of them was killed by their mother, the remaining cub was hand-fed. Mike the leopard was a favourite of the zookeeper’s daughter and, in her words, became “tame, affectionate and just like a big cat”. Even at two years old when returned to a cage he seemed content to be there and, she said, “I can put my hand in his mouth, and he never bites.”

. . .

The zoo on the Queen’s Domain finally closed in November, 1937, after waning popularity and the Depression resulted in increasing protests about its cost. As early as 1934, Alderman Harvey described the zoo as “this ghastly failure” and later deemed it “a gaol for animals”. Alderman Valentine felt Hobart should not attempt to have another Taronga Park. There were also concerns, expressed in a letter to The Mercury, that the animals should not be sold to circuses, where they would be “dragged around … in smaller, darkened cages, with the constant clamour of trains and ships, after their quiet life in tree-shaded grounds”.

The monkeys were bought by Adelaide Zoo, hundreds of birds were auctioned, and the surviving zebra was also sold to Adelaide Zoo, where he lived for another nine years. The polar bears were received at Wellington Zoo after great difficulty enticing them into a crate for shipping. And, sadly, after unsuccessful attempts to sell them to mainland zoos, the lions Betty and Sandy were shot … like so many other creatures that had lived at the zoo.

. . .

As we leave, a flock of rosellas clamours in the trees and seed husks fall to the ground. The vacant site has now become a refuge for threatened birds, as well as eastern barred bandicoots and eastern quolls – both extinct on the mainland of Australia.

But these animals are now hidden by long grass, just as they were long before a zoo was there.

Dr Carol Freeman is a Hobart-based researcher and writer. Her work appears in books and academic journals, exhibition catalogues and art magazines on topics that connect art, science and history. Her book "Paper Tiger: How Pictures Shaped the Thylacine", is published by Forty South. More about her can be found at carolfreeman.net.au.

Brendan Lennard is a former senior cultural heritage officer with the City of Hobart. It was during this time that he developed a fascination with the Beaumaris Zoo. For more than 25 years, he conducted tours of the site and researched its intriguing history.