A few years ago I was living a life of blissful retirement in the south-east of France when I became interested in my family history. I had accompanied my wife to France so she could improve her French. This part of the country – the Department of Languedoc-Roussillon – is the land of bullfighting, rugby and robust red wines. Vineyards dominate the landscape and, on the coast, white sandy beaches abound.

With plenty of time on my hands, and ignoring advice that family history research can be both addictive and consuming, I embarked on my road of discovery. Five years have passed and that journey has presented fascinating and surprising outcomes, particularly concerning many of my Tasmanian ancestors.

This story concerns just one.

Henry Jones, my great grandfather, was honoured with a knighthood by King George V in the New Year’s honours list of 1919. The citation read, “An architect of his own fortunes and his ability and enterprise had a giant influence upon the progress of Hobart and the state of Tasmania.”

Historical records of the time indicate Sir Henry’s entrepreneurial flair, sound investments and general business acumen made him an icon of Tasmanian commercial life over a period of 30 years.

. . .

Sir Henry Jones was educated in Hobart at Mr Canaway’s School where, anecdotally, he showed an aptitude for commercial subjects. He began work in 1874, aged 12, at George Peacock’s jam factory, pasting labels on jam tins, and within a few years was reputed to be an expert jam boiler. Promotion to factory foreman came in 1885, and in 1889, when Peacock retired, Henry took control in partnership with others and renamed the company H. Jones & Co.

Modernisation and diversification followed, resulting in a more viable operation. During this period, Henry became a leading Australian financier and one of the early advisors to the Commonwealth Bank. At all times he was a strong advocate and supporter of Tasmanian commercial activity and gave with quiet generosity to the Methodist Church and many charitable institutions. He accepted appointment to the Tasmanian Executive Council in 1924. He died in Melbourne during a business trip on October 29, 1926, of a heart attack. Such was his esteem and reputation, more than 10,000 citizens lined the route of his funeral procession.

As a direct descendant of this great Tasmanian, I was keen to find out more about the man and what influences he may have had to rise above his humble beginnings. My research produced a great surprise, and only increased my admiration for the achievements of the man.

The birth of Henry Jones was registered on August 18, 1862, and the original certificate records that he was born on July 19 of that year in Melville Street, Hobart. His father was John Jones and his mother Emma Jones (nee Smith). This information was included in a 1973 paper by John Reynolds entitled Sir Henry Jones, K.B. in the Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, and later repeated by Reynolds in his contribution on Henry Jones to the Australian Dictionary of Biography.

My research, however, shows that Henry Jones’ mother’s maiden name was Mappison, and that neither John nor Emma came from Wales as a married couple, as claimed by Reynolds and repeated by many other writers (eg, I Excel – The Life and Times of Sir Henry Jones, Bruce Brown).

. . .

My new information has significant consequences.

Family papers from other present-day ancestors of Sir Henry Jones, together with records provided to me by the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, reveal John and Emma Jones produced eight children – three boys and five girls – between 1853 and 1872. No official or archival records for the first born, Elizabeth, or the last born, Fanny, have been located and, quite possibly, these births were simply not registered. However, handed-down family records confirm their birth and marriage details.

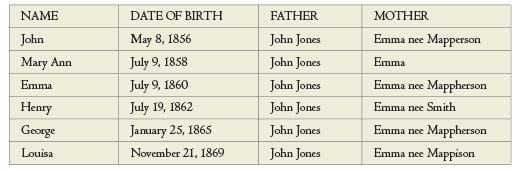

Birth records obtained through the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office for the other six children reveal, inter alia, the following:

Based on these birth records, it could reasonably be concluded that Emma’s maiden name was Mappherson or similar. It is not known why Emma’s maiden name is recorded as “Smith” on Henry’s birth record, and it can only be surmised why this occurred.

Once these birth records had been examined, and it was conclusively proved that Emma’s surname was not Smith, but Mappherson, or a variant, I turned my attention to when and how John and Emma arrived in Tasmania. Initial efforts of checking 19th century arrivals lists proved unsuccessful, as no definitive record could be located, either for a married couple from Wales, or records for individuals. At this point I began to check Tasmania’s convict records, on the chance that John and Emma were reluctant arrivals to the colony. It was common in the early 20th century for Tasmanian families to gloss over, or hide, convict ancestry, so whilst I assumed John and Emma were free settlers, it was worth checking the records.

Initially, attempts to find the right John Jones were unsuccessful, as there were more than 350 convicts bearing this name who arrived in Van Diemen’s Land between 1804 and 1852. However, records for Emma were more promising. A convict record for an Emma Mappison was located, and this was the same name as recorded on the birth record for baby Louisa. Significantly, no trace could be found of an Emma Mapperson or Emma Mappherson.

Subsequently, a Marriage Office marriage registration, transcribed from the original church record in the names of a John Jones and Emma Matheson, and produced by the Archives Office of Tasmania, was purportedly the marriage record of John and Emma Jones. This marriage record indicates this couple were married at St Georges Church, Battery Point on September 8, 1853. The significance of this record was established when the original church marriage registration was obtained (see below).

The most important and revealing item on this document is the signature of the bride which shows her maiden name to be Mappison. Elsewhere it can be seen her maiden name is spelled Matheson, the reason for which was established soon after.

Archival records reveal that this marriage occurred only after being sanctioned by the State. This permission, given on August 3, 1853, can be found in the original records of Convicts Applications for Permission to Marry (Con.Ref: CON52/1/6), which reveals the application was submitted by John Jones and Emma Matheson. Hence the reason for this incorrect spelling occurring on the marriage certificate and record – this incorrect spelling probably arose through either poor elocution or confusion emanating from a strong regional accent.

In recent times the Archives Office of Tasmania has digitised convict records, including applications for permission to marry. The digitised record of this application shows the correct spelling of Emma’s maiden name (see below).

The convict permission to marry register also detailed the ships which brought John and Emma to Tasmania, which meant their convict records were easy to locate, and many of my outstanding questions would now be answered.

Emma arrived in Hobart first on June 30, 1848, on the ship Elizabeth and Henry. She was 18 and had been sentenced to seven years for the theft of a cash box worth £300 from her former employer. The transcript of her trial can be found on the Old Bailey website. Her time as a convict was uneventful.

Emma also had a prior conviction for theft when aged 14. The trial record at Huntingdonshire Library and Archives, Cambridgeshire, reveals Emma, together with Ann Searjeant, was convicted for the crime of “theft of wearing apparel at Stanground”.

Emma was born and raised in Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, the sixth of eight children born to John and Margaret Mappison (nee Johnson), who were married at St Antholin, London, in 1817. Her father was born in 1791 and worked as a grocer. As an aside, Emma’s brother Henry Mappison was also transported, aged 15 years, arriving in Tasmania on September 23, 1843, on the Asiatic. His offence was theft of gold valued at £5/10/-.

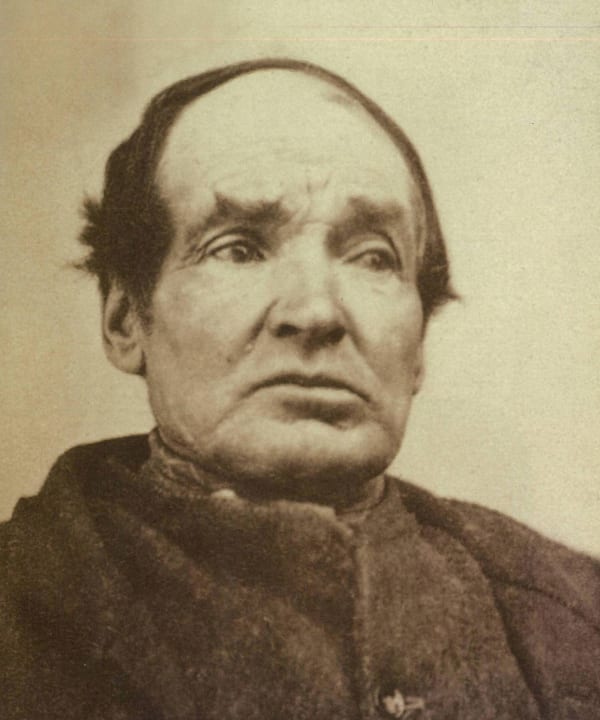

John Jones arrived November 14, 1850 on the ship William Jardine. He was 32 and had been sentenced to 10 years for stealing a gold watch. He was a small man, standing just 4ft 7½in (1.41m).

His English hulk records note the fact that he was “deformed”, and his Tasmanian records reveal that his back had been broken at some stage.

Jones could claim the dubious distinction of belonging to that small band of convicts who were transported more than once, for he was initially shipped abroad as a convict to Bermuda in July 1839, after being found guilty by a court in Liverpool of stealing a coat and hat. In Bermuda he laboured for seven years, helping to build the naval dockyard on Ireland Island.

Jones’s Tasmanian convict record reveals four offences, all involving drink, before he was granted a conditional pardon in August, 1853. After receiving his certificate of freedom in July 1857, he appears to have stayed out of trouble until September 1865, when he was sent to Campbell Street gaol in Hobart for four years on a charge of forgery and uttering. Subsequently, in July, 1872 he was sent to Port Arthur for five years for a similar crime. It is little wonder his son Henry had joined the workforce by the age of 12 in 1874.

It was in 1874 during his Port Arthur incarceration that John Jones was ordered to sit for a photographic portrait. This is the image of John Jones reproduced with this story, the image of a reluctant pioneer and an Old Crawler, a term used dismissively to describe the ageing survivors of the convict system.

Even at this late stage, I was challenged by the ubiquitousness of the name John Jones, as there were two convicts with that name aboard the William Jardine. However, the record-keeping of the Convict Department in the 19th century decreed that when this happened, individuals were identified by the numbers (1) or (2) on all official paperwork. John Jones had been correctly recorded on the permission to marry record as (1), and so I could finally identify the correct man in the William Jardine records.

John and Emma Jones share the same plot at Hobart’s Cornelian Bay Cemetery, the records for which reveal John was buried on February 11, 1909, the day before Emma. John actually died on March 6, 1886, and my research revealed that his body was moved from its initial resting place at Queenborough Cemetery when his wife died.

There has in recent times been a reversal of attitude towards our convict past. Today, Tasmanians are both interested in, and proud to acknowledge, their convict ancestors. In earlier times, and especially in the period immediately after transportation ceased, any such association was hushed up. It is unlikely, however, that Sir Henry Jones was able to do this, which makes his success all the more remarkable.

Craig Sampson was born in Hobart in 1949 and lived for 16 years in Lower Sandy Bay, an area he describes as “a boy’s paradise”. He attended Waimea Heights Primary and Hutchins School before his family moved to Melbourne.

The author wishes to offer special thanks to Ms Elizabeth Ballard and Dr Alex McLaren for their encouragement and assistance in the research and writing of this story.