Thirty kilometres north-west of Wynyard, the Bass Highway sweeps down from the Sisters Hills onto Fords Plain. On the right is the Rocky Cape roadhouse. One kilometre on, the other roadhouse, the Detention River Store, comes into view on the left. As we shoot out onto the open span of the bridge, I ask the usual question, “Is there anyone at our fishing spot?” There is a pause while young eyes feverishly scan the scene. “Nope Dad, all clear.” The road swings around to the right in a wide arc around the shallow inlet and we slow, as we approach the turn off to Hellyer.

The north-west Tasmanian coastal hamlet of Hellyer is named after Henry Hellyer (1790-1832), surveyor and architect with the Van Diemen’s Land Company. His feats of endurance exploring the wilds of north-west Tasmania, and the tragedy of his death, have inspired books, academic papers and a play. Hellyer is an unassuming cluster of beach houses on the western side of the mouth of Detention River. Most are the traditional mix of fibro, corrugated iron and weatherboard, with boats on trailers the most common garden ornament. A low dune separates the houses from the long gentle curve of Hellyer Beach. On the eastern side of the river, Hellyer Beach is mirrored by Forwards Beach, stretching away towards Rocky Cape.

At low tide the river is a slender, rusty red snake that slithers back and forth across the sandy flats of the estuary, making a dirty smudge were it disgorges its forest tannin-stained waters into the sea. While we fish, the orange-red river water fades as it is pushed back by the incoming tide. Later, walking back to the car, we emerge from the bush with our ears ringing from the static of cicadas and hum of bees in the melaleuca. As we top the small rise, I always pause to take in the view. In just a few hours the whole estuary has filled and is now a gorgeous aquamarine. I never tire of this vista – most likely because I’m usually carrying a good feed of yelloweye mullet, Australian salmon and the occasional big flathead.

Over the years, I’ve driven to Hellyer a thousand times; maybe 50 times in real life and the other 950 in my mind’s eye. It’s my happy place, where I go at three in the morning when I’m being haunted by some dark phantom of the mind. After hours of tossing and turning, I’ll get up and go to the kitchen and gaze out the windows into the Melbourne night. Then I’ll return quietly to bed, close my eyes, breathe steadily … get down the fishing rods and drive to Hellyer.

. . .

When I first heard about Henry Hellyer, I wondered if he had a happy place to go to when the phantoms came for him. God knows, he needed one. During the early hours of Sunday, September 2, 1832, he put a horse pistol to his head and blew his brains out.

When Hellyer arrived in Tasmania in 1826 he was in his mid-30s. In those early days, his boss, Edward Curr, was pleased with his work and admired his personal qualities. Hellyer wrote with eloquence about his new home. He decorated his diary entries with the eye of a surveyor and the hand of an artist.

That changed as the years passed, however, and by the time he turned 40 he felt his world collapsing in on him and he sank into depression. In the end, he could only see one solution.

Hellyer blamed himself for the VDL Co’s failed venture to rear sheep on the uplands in the shadow of Cradle Mountain. The Company was established in 1824 in order to cash in on the textile boom in England. Its directors speculated that their Royal Charter would grant them extensive sheep country in the new colony. Instead, they were allocated a huge tract of the remote and inhospitable north-west. Hellyer’s job was to explore this daunting wilderness and find grasslands suitable for running sheep. His most famous expedition was in early 1827, a trek on foot from Circular Head to the landmark “peak like a volcano” sighted by Bass and Flinders in 1798. Hellyer climbed mountain ranges, forded wild rivers and struggled for weeks through dense scrub and forests where “the foliage is impervious to the rays of the sun”.

In a stroke of good fortune that Burke and Wills would have appreciated, Hellyer and his two exhausted, half-starved companions limped back to their base camp at the foot of the Dip Range just in time. The men that Hellyer had left there with supplies and horses had “given up all hopes” and were preparing to leave the next day.

However, to Hellyer these dangers and privations had been worth it. He had climbed the peak on February 14 and named it St Valentines Peak. From the summit he had seen the open country his employers were so desperate for. He named these areas the Surrey and Hampshire Hills in honour of his home in southern England. What he actually saw was the summer hunting grounds of the Noeteeler people.

What he actually saw was the summer hunting grounds of the Noeteeler people.

Hellyer had encountered no Aborigines on that expedition, but he felt their eyes on him as he entered their huts and raked through the ashes of their campfires. The Noeteeler spent the winter on the coast between Emu Bay and Port Sorrell feasting on southern rock lobster, abalone, oysters and waterbirds and their eggs. Each summer, after the snows melted, they moved inland to hunt kangaroo, emu and wallaby in the high grasslands that Hellyer saw from the peak. For hundreds of generations they had kept these ancestral lands open and the pasture refreshed by seasonal burn-offs – “fire-stick farming”.

Upon Hellyer’s return to Circular Head, an excited Curr ordered him to cut a road to the Hampshire Hills from Emu Bay. Work commenced in July 1827 and it was difficult, dangerous and monotonous. Hellyer and his men slaved for months in the dark forest felling the massive trees. They were always short of rations, it rained incessantly and they were forever cold and damp. Eventually, the road was completed. In January 1828, Curr came to inspect, but he wasn’t impressed. The coarse native grasses and damp ground may have been fine for kangaroo, but not for sheep. The following five winters saw the Company lose about 4,000 sheep to disease, the bitter cold and thylacines. The land was never suitable for sheep or cattle. These days, the Surrey and Hampshire Hills are largely under forestry plantations.

Just before the end, there was a glimmer of hope for Hellyer when he was awarded a prized government job in Hobart. But there was jealousy among his fellow officers and hurtful rumours circulated in the mess. The whisperings were that the unmarried Hellyer was homosexual. We will never know whether this was true or not, but it didn’t matter. Hellyer knew that he would be ostracised and laughed at behind his back. Three days before his death, Hellyer demanded Curr investigate to find out who was slandering him, but Curr blithely dismissed his concerns. Well past midnight on Saturday night, with the ship that was to take him to Hobart bobbing at anchor, Hellyer finally finished the suicide note he had been working on for several days. When the door to his room was forced open in the morning, a gruesome scene was revealed. According to a report, “He had put the pistol to his head and had blown the whole skull to atoms.”

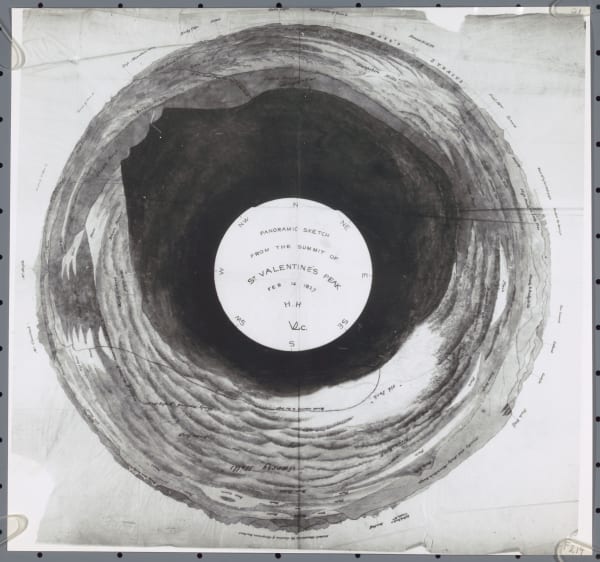

As I learned more about Hellyer, I realised he did have a happy place – and it wasn’t far from mine. He found bittersweet solace on the lonely summit of St Valentines Peak, where on a clear day you can take in a breathtaking, 360 panorama of half of Tasmania. Facing north, you start with Table Cape jutting out into Bass Strait. Turning right, you’ll see the mouth of the Tamar and Ben Lomond in the east and then Mt Rolland, the Black Bluff Range and Cradle Mountain. Due south are the distant high peaks near Macquarie Harbour. West is Mt Norfolk, the Dip Range and then the Sisters Hills, before you are back at Table Cape. If you turn back to the left and squint, you can almost see where I stand fishing at the mouth of Detention River.

I’ve never climbed St Valentines Peak, but I know you can see all this because the National Library in Canberra holds Hellyer’s amazing and beautiful circular panoramic sketch. Look at the panorama and climb St Valentines Peak with Henry Hellyer. Stand next to him and feel the wind on your face and let the silence into your soul. Then, ask Henry how he is feeling. And just listen. No matter what he says, don’t judge him. We all know Henry. I’m Henry. You’re Henry. A colleague, friend or family member is Henry. The good news is that it isn’t 1832. Let Henry know you care and there is help close at hand.

If you see parallels between Henry Hellyer’s story and your life, or that of someone you know, there is help available, 24 hours a day. Call Lifeline Australia on 13 11 14 to talk to someone trained to help in a crisis. Other resources and immediate support are available from organisations like BeyondBlue. You can also talk to you GP about how you are feeling.

Dr Terry Mulhern is a biochemist, university educator and researcher. If he isn’t in his office or somewhere taking a class, look for him in the basement of the University of Melbourne’s Baillieu Library under 994.6 History, Tasmania. He was the 2018 winner of the David White Award for Teaching Excellence, the University of Melbourne’s highest honour for teaching in Health, Science, Agriculture and Veterinary Science. Terry Mulhern was born in north Queensland and has worked at universities in the UK and around Australia, but his heart is in north-west Tasmania.