Nineteenth-century histories of Tasmania were generally written by gentlemen sheep farmers and urbane colonial citizens. Thus narratives that suited a land-based history set the scene for a narrative copying exercise that has persisted into the 21st century. Within these, “the Aborigines” are often a homogenous mob, indistinct in a sort of timeless migratory holding pattern, until prompted to reactive hostility by settlers and their servants. James Kelly’s voyage reveals a more complex story.

It has been a big year for battle anniversaries – Agincourt, Waterloo, Gallipoli, Recherche Bay. There is no prize for guessing which one has not been the subject of serial television commemorations and newspaper specials.

A skirmish on Tasmania’s south-eastern coast on December 13, 1815, has largely been overlooked. It is unknown to most military enthusiasts. No formal armies were involved in the battle of Recherche Bay, but it marks the moment when frontier conflict in Van Diemen’s Land shifted decisively from operations at the borders of European settlement to conflict deeper within the Aboriginal landscape.

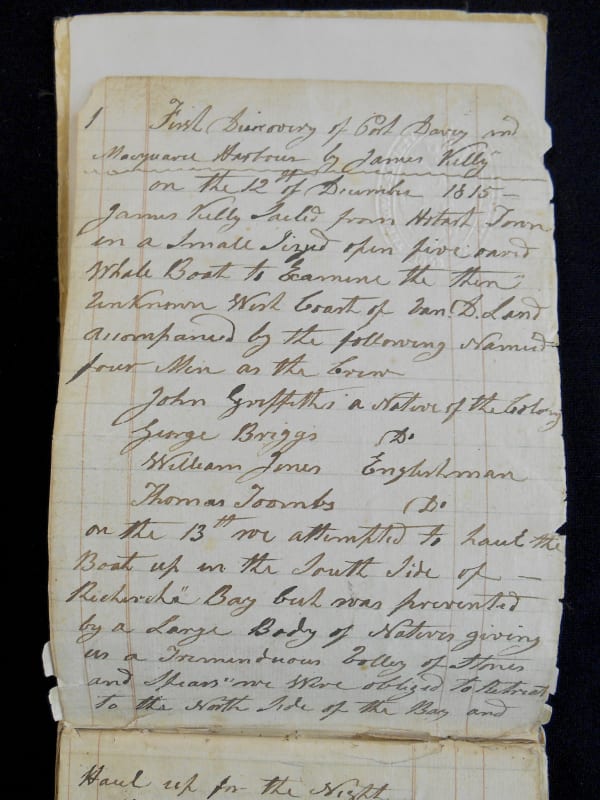

The incident occurred one day’s sail from Hobart. Journeying by muscle and wind in “a small sized open five oared Whale Boat”, the five occupants were prevented from making an afternoon landing at Recherche Bay “by a Large Body of Natives”. So wrote James Kelly, the skipper, who added that his failed landing and prompt retreat was because the Aborigines had driven the would-be campers away with “a Tremendous Volley of Stones and Spears”.

Such was the brief description of that first moment of conflict. It was recorded in Kelly’s journal, a handwritten account of his voyage in the summer of 1815-16. He, his journal and his voyage are famous in Tasmanian history for being the first known circumnavigation of Van Diemen’s Land. And here, on the first page of one of the most important historical chronicles of early colonial Tasmania, is evidence of Aborigines offering resistance to incursions into their territory.

Beyond the immediate limits of British settlement, Recherche Bay is a place named and known for French scientific expeditions conducted in the 1790s. Such French attentions, coupled with the new geographical certainty of the early 1800s that Van Diemen’s Land was an island, helped prompt the British to colonise Tasmania to pre-empt rival attempts.

Yet the penal settlement was more than 10 years old before its coast was properly investigated by Kelly and his crew. This voyage, recorded in that small, old, handwritten journal now kept securely in the University of Tasmania Library’s Special and Rare Collections, captures details of a triumph of colonial nautical exploration and coastal navigation.

Although forced to spend that first night on the other side of Recherche Bay, and experiencing later adventures like being detained by nervous guards in George Town, stepping into the politics of inter-tribal conflict among Aborigines and repeatedly overcoming dangerous conditions and uncharted shores, the voyagers safely re-entered the Derwent estuary “Forty Nine Days” later, on the afternoon of January 30, 1816. During their travels Kelly and his crew had discovered and named parts of Tasmania’s south and west coast, including Port Davey and Macquarie Harbour, named for the Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen’s Land and Governor of New South Wales respectively. At that time the bigger colony still ruled the smaller, a fact hinted to by the nomenclative honours, which to some modern sensibilities suggest colonial sycophancy.

The chronicle of Kelly’s voyage was clearly written for a wider audience. Although he signed his name to the end, in the same handwriting and ink as the body of the text, he wrote using a mixture of third person and collective pronouns. Yet in conducting such a trip, and just as importantly through recording it, Kelly provides glimpses of the original Tasmanians encountering and adapting to the early colonial enterprise, even though that was probably not his primary objective.

For instance, the day after being bombarded away from that part of Recherche Bay, Kelly and his crew got “a Friendly Reception from a Large Number of Natives” at “a Small Sandy Bay to the Northward of the De Witt Isles”. There was an exchange of gifts – not all encounters were violent or filled with mutual suspicion.

Several days later the whaleboat was heading north from the recently-named and just-explored Port Davey. One evening Kelly and crew landed on a small island a little off the coast. Two Aboriginal men were there, and each group was surprised to see the other. But again Kelly offered gifts, giving the men some swans killed recently in Port Davey.

Dead swans saved the day – in early January when, shortly after exploring Macquarie Harbour and harvesting some swans there, the sailors “were acosted [sic] by six huge men”. Each had a spear in the right hand, two reserve spears in the left, and a hostile attitude. But gesturing them over, and showing the swans, Kelly and crew appeared to have calmed the situation. The Aborigines approached. Kelly now saw that each dragged another spear with them by their toes. According the Kelly, they now managed to trade four swans and a wombat for “all their spears”.

Even with the Aborigines disarmed by a factor of twenty-four spears, Kelly and crew spent a nervous night, drying and attending to their own weapons, making sure they were in full working order. But they were left alone, and continued their journey the next morning.

Up the west coast the sailors had seen a number of fires, of a sort they recognised as made by Aborigines. In fact one of the men, George Briggs, had long familiarity with Aboriginal peoples, having even fathered children with Aboriginal women in northern Tasmania, and seemingly being integrated into some Aboriginal kinship relationships. As the whaleboat rounded Cape Grim and re-entered familiar colonial territory, Briggs became a significant figure within Kelly’s narrative.

The first real skirmish between the sailors and Aborigines occurred when, after witnessing a dance performed for their benefit, a tussle over swans resulted in gunshots from a nervous and pistol-wielding Kelly. Holding the swans even as there were attempts to snatch them from him, Briggs was at one point dragged along the ground. The surprising effect of gunpowder seemed to panic the Aborigines, saving Briggs from further harm.

Not long afterwards, the sailors were detained at George Town, and accused of being bushrangers.

In charting the south, west, and north-west coasts of Tasmania they had crossed through a sequence of cultural territories that are still relatively poorly understood. In moving from the settlement of Hobart Town to George Town the whaleboat traversed a large amount of coastal territory that was nominally British (at least to the British), but which was in actuality still definitively Indigenous. And within this broader pattern, it is perhaps unsurprising that the most hostile engagements Kelly and crew had with Aborigines were in those areas closest to the major settlements.

Tasmania’s colonial expansion was more coastally orientated than often allowed. Nineteenth-century histories of Tasmania were generally written by gentlemen sheep farmers and urbane colonial citizens, or at least funded by or pandered to that audience. Thus narratives that suited a land-based history set the scene for a narrative copying exercise that has persisted into the early 21st century. Within these, “the Aborigines” are often a homogenous mob, indistinct in a sort of timeless migratory holding pattern, until prompted to reactive hostility by settlers and their servants. James Kelly’s voyage reveals a more complex story.

Eventually the whaleboat at its crew departed George Town and continued eastwards. Landing at “Ringarooma Point”, they “suddenly fell in with a Large Mob of Natives who at the first appearance seemed Hostile”. But the Aborigines recognised Briggs, and the chief, Lamanbunganah, “seemed delighted at seeing Briggs and told him that he was at War with his own Brother”. Briggs knew Lamanbunganah’s rival because, as Kelly pointed out in his narrative, Briggs “had on the Islands two Wives and five Children”. This was home territory for Briggs, who had lived in northern Tasmania for a time working as a sealer. Lamanbunganah was his father-in-law.

Lamanbunganah then tried to enlist Briggs and company in the war. Apparently there were reports “that five or six white men well armed” were aiding Lamanbunganah’s rival, Tolobunganah, so he was hoping to enlist his own white men and their guns to his cause. The entreaty did not meet with Brigg’s immediate acquiescence, clearly irritating Lamanbunganah, who accosted Briggs by reminding him “that he had often before gone with him to fight other Tribes when he wanted Women”. It was a pointed comment, which Kelly later filled out with more detail, building up a picture of a fairly wild and rough and ready existence for the sealing men of the 1800s and 1810s.

Kelly’s crew was surrounded by Lamanbunganah’s men. They eventually managed to escape, continue their voyage and return to Hobart Town, but the incident reveals how, within a decade, the European settlement and its economic tentacles related to Indigenous Tasmania in complex ways. Europeans and colonials variously became participants, observers, recorders, friends and enemies. James Kelly proved to be all five, leaving brief records of minor skirmishes, and hints of battles and wars that rarely get commemorated.

Nick Brodie describes himself as a professional history nerd. He has a doctorate in late medieval vagrancy law, is a leading expert on the history of poor boxes, and is the author of acclaimed popular histories Kin: A Real People's History of Our Nation and 1787: The Lost Chapters of Australia's Beginnings. His latest book is The Vandemonian War: The Secret History of Britain's Tasmanian Invasion, which uses a wealth of new archival material to re-write Australia's most infamous colonial war.

This article was first published in Issue 79 of Forty South print magazine.