We planted a Tasmanian blue gum in our garden when we lived in Sandringham, a bayside suburb of Melbourne. It grew next to the high wooden side gate and overhung the wide nature strip that characterises the area.

Two boys spent countless hours in the arms of that enormous tree, regularly climbing as high as they could to keep an eye on the neighbourhood, like cats on a cupboard. It was their cubby house and hiding place – adults didn’t tend to look up and its boughs were inaccessible to them.

Tasmanian blue gums can grow to 90 metres and are among the largest trees in the world. Soon after we moved to the Sandringham house in the mid-1970s, we were given a metre-high sapling with the label “Eucalyptus globulus (Tasmanian blue gum)”. We placed it close to the boundary of our large corner block so it would have plenty of room to grow without shading the house. And grow it did!

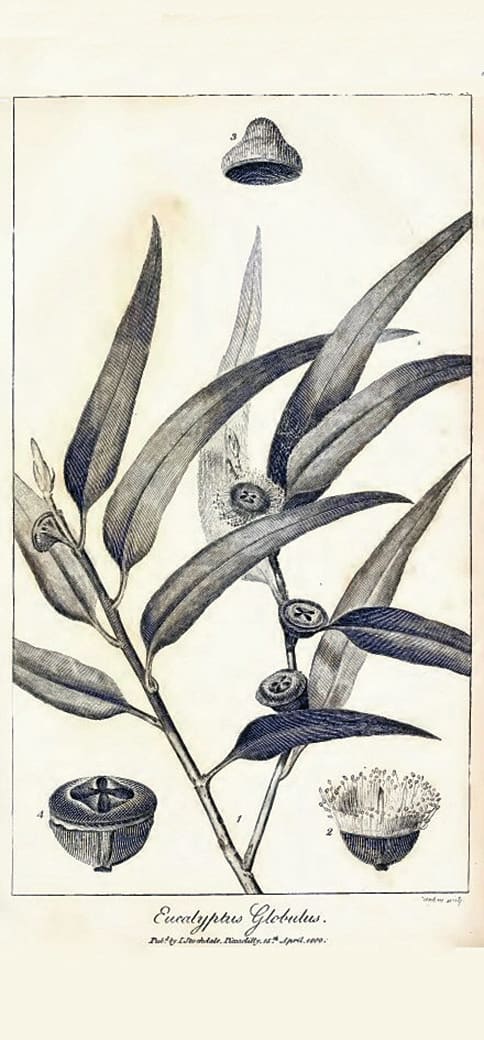

Of all eucalypts, Tasmanian blue gums are the most common of the species now cultivated throughout the world. The first seeds known to have been taken to Europe were collected at Recherche Bay in southern Tasmania on May 6, 1792, by French naturalist Jacques Labillardière, on the D’Entrecasteaux expedition. In his popular account of the voyage he remarked, “This beautiful tree, which belongs to the tribe of the myrtles, has a very smooth bark,” and, “The trunk, which is very straight, at least to one half of its height, might be usefully employed in ship-building, and especially for masts.” He named the species for the shape of the fruit: the Latin globulus referring to coat-buttons common in France at that time.

By 1810 they are rumoured to have been among the many exotic trees planted at Château de Malmaison, the large manor house in Paris that Josephine bought for her husband Napoleon Bonaparte. Several years later Napoleon spent his last days there with the kangaroos, emus, black swans and other imported fauna that roamed the estate’s extensive grounds.

Soon the gum’s high density timber became prized for shipbuilding and wharf piles, which the British Admiralty considered “the most durable that had ever reached British shores”. It was also in demand for street paving, railway sleepers and mine supports, as well as pulp for paper. As testament to its numerous uses, ease of cultivation and adaptability to a wide range of conditions, by the end of the 19th century E. globulus had been introduced to countries in Europe, South America, North America, Africa and Asia.

In his book Emigrant Eucalypts, Robert Zacharin traces the spread of the tree up until 1978. After cultivation near major Mediterranean ports, France became a key distribution point for blue gums worldwide. Later Ferdinand von Mueller, director of Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens, enthusiastically promoted its dispersal, considering the species the “Prince of Eucalypts”, while Labillardière himself urged its cultivation in France in a letter written just before his death. By 1829 there were plants growing in the Camaldoli Gardens near Naples. They were sown around Rome for their reputed anti-malarial benefits, including “the power of destroying the miasmatic influence of marshy districts”. In the South African Governor’s garden, near Cape Town, nine plants from Australian seed raised in Mauritius flourished. The species was introduced to Spain in 1847 and today 500,000 hectares have been planted there – roughly the same number as Australia has in plantations.

In Ethiopia, a country close to the equator, Tasmanian blue gums were introduced at the turn of the 20th century as a solution to the almost complete denudation of the country’s native vegetation as a result of unrestrained harvesting. They provided fast-growing fuel, charcoal and poles for fencing and home construction and were particularly important in the establishment of Addis Ababa, the country’s first city that changed the habits of a nomadic population. It remains the major commercial species. Ironically, the locals call the tree ‘Nech-Baharzaf’ (White Eucalypt) and owning a stand is considered a sign of wealth. In 1990 an estimated 100,000 hectares of the species were under cultivation in Ethiopia.

Portugal and Spain combined have by far the world’s largest area of E. globulus – 1.2 million hectares. Introduced to Portugal in 1866, they supplemented poplars as a means to control soil erosion caused by the flooding of the country’s largest river, the Mondego. Later, land was bought up by Scandinavian timber companies and planted for wood pulp.

In the 21st century, global cultivation of Tasmanian blue gum for a wide variety of purposes is estimated in excess of 2.4 million hectares. About 50 per cent of these grow in the Iberian Peninsula.

. . .

The international importance of Tasmanian blue gum has seen it become a model species for research in forest trees. In a valuable convergence of botany and social history, investigators at the University of Tasmania, including one of the boys who spent so much time up that tree in Sandringham, are using DNA fingerprinting to trace the Australian origins of E. globulus worldwide. Although its native range includes the Bass Strait islands and the south-eastern mainland of Australia, this research suggests introductions were overwhelmingly sourced from seed collected in southern Tasmania.

Intriguingly, it also reveals that some of the eucalypts growing in France and Italy most likely came from seed collected in the vicinity of the D’Entrecasteaux Channel, where the French expedition captained by Nicolas Baudin landed. This suggests that the French samples may have derived from this voyage rather than Labillardière’s earlier collection, 60 kilometres south. It’s remarkable to consider that tiny seeds from blue gums collected by French explorers in the Channel in 1802 have produced the enormous trees now growing in parts of Europe.

Long before Europeans encountered the “blue gum”, Aboriginal Tasmanians had used its close-grained wood for spears and bark to make canoes. They also applied its leaves as poultices for wounds, inflammation and rheumatism and inhaled the odours from boiling them to treat chest colds and headaches. Today, worldwide production of eucalyptus oil continues to be dominated by the species and studies have shown that the cineole content of these oils has antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, expectorant and other medicinal properties.

It’s not surprising, then, that early European sources maintained the vapours released by eucalypt forests in a blue haze resulted in an exceedingly healthy atmosphere.

The Tasmanian blue gum was proclaimed the floral emblem of Tasmania in 1962, but is rarely used on government publications or on other official items – the Tasmanian tiger having more appeal. The first hardwood forest tree to have its chloroplast genome sequenced was a blue gum. The oldest tree in the Royal Tasmanian Botanic Gardens, it was cut down in 2006 as it had developed fungal rot in its large trunk. When the DNA analysis was completed, clones of the tree were produced by the University of Tasmania, one of which has been planted on the Garden’s Eucalyptus Lawn and another near the University Club in Dobson Road, Sandy Bay campus.

Meanwhile, in the US and several other countries where Tasmanian blue gums have naturalised, it is sometimes considered a problem tree, which has sparked debate regarding its invasive potential. The risk of invasion, however, is currently assessed as “limited” by the Californian Invasive Plant Council. It was planted by farmers in California during the 1856 gold rush, making use of its ability to absorb groundwater and reclaim wetlands. The rapid growth, dense stands and thirsty nature of E. globulus made it an ideal candidate for this job. In California today there is little interest in the trees except as windbreaks or ornamentals, but their ability to thrive in difficult conditions, to out-compete native plants and to re-sprout after wildfires has resulted in the species becoming a familiar element in the landscape. They are survivors.

. . .

While there has been concern about blue gums altering ecosystems in places like California, just as there is about introduced flora and fauna in Australia, they are a vital part of the Tasmanian biosphere. This is most poignantly illustrated by the reliance of the critically endangered swift parrot on E. globulus stands in eastern Tasmania. The swift parrot is a migratory bird that winters on the mainland of Australia, but breeds and feeds in its home state from August to February where, paradoxically, blue gums often grow on land that is continuing to be cleared. Nest sites inside hollow tree branches or trunks in very old or dead trees can take hundreds of years to form and the parrots mainly feed on the nectar of E. globulus flowers. It is now a national priority to conserve their blue gum habitat, including protecting land through covenants, management agreements, changes to the forest practices system and education programs that encourage the retention of old trees and planting of new ones.

Migration from place to place is the practice of humans as well as birds and, as we have seen, trees also migrate when seed is collected and then propagated far away. The blue gum in the garden at Sandringham remained until a few years ago when, like so many other large trees in the suburbs, it was felled. Then, on a very recent visit to Melbourne, I noticed the stump had, true to its reputation, re-sprouted. A vigorous head of blue-green leaves could be seen above the high fence surrounding our old house . . . but the lush, young growth was out of reach and the new owners were not there to pacify a barking dog.

Maybe another time, I can pick the shoots of that resilient Tasmanian blue gum and crush the leaves to release the distinctive, pungent essence of home.

Carol Freeman is researcher and writer who has lived in Hobart for over 30 years. Her work appears in books and academic journals, exhibition catalogues and art magazines on topics that connect art, science and history in innovative and provocative ways. These include a co-edited book Considering Animals: Contemporary Studies in Human-Animal Relations, essays such as Is this Picture Worth a Thousand Words? in Australian Zoologist, catalogue essay Reconstructing the Animal for an exhibition at Tasmanian College of the Arts and book reviews for Historical Records of Australian Science. Her major publication, the book Paper Tiger: How Pictures Shaped the Thylacine, is published by Forty South. Since 2015 she has been a regular contributor to Forty South on a variety of subjects.