From Deloraine, Mole Creek Road rises gradually until, nine kilometres west of town, you pass through the narrow gap between Gardners Ridge and Needles Ridge. Then the road falls gently towards Chudleigh. Although most will be oblivious to it, this is one of Tasmania’s great divides. This ridge line is the watershed between the Tamar catchment and the “western rivers”.

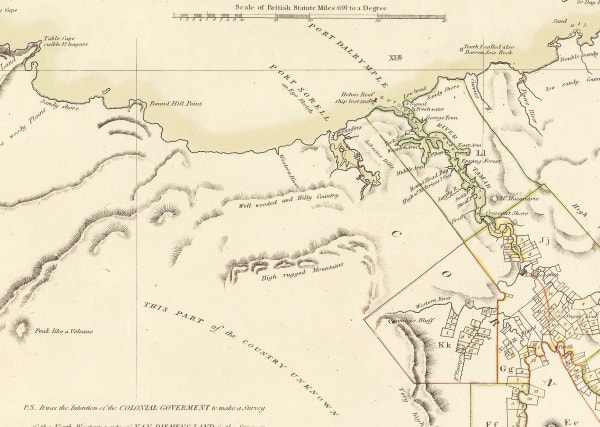

Before the mid-1820s, maps of Van Diemen’s Land were largely blank west of the line joining Hobart to Launceston. Even the rivers emptying into Bass Strait were simply, “First Western River”, “Second Western River” etc.

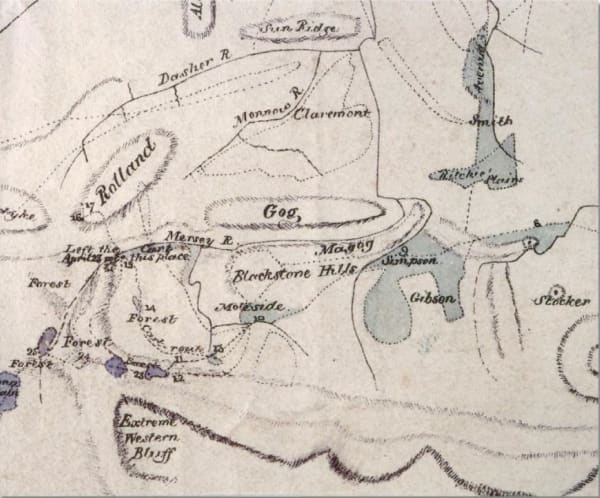

Beyond Needles, the creeks drain into the “Second Western River” – the Mersey. The Mersey starts high on the central plateau. After descending from the high country, its passage northward is blocked by Mt Claude, Mt Vandyke and Mt Roland. These mountains were named in 1823 by Captain John Rolland (whose name is now misspelled in perpetuity).

At the foot of Vandyke, the Mersey turns east and finally breaks through the mountains via a chasm between the peaks of Gog and Magog. Rolland named them after the barbarian kings Alexander the Great imprisoned behind a massive iron gate spanning a similar canyon in the Caucasus Mountains.

For Tasmanian Aborigines, the Gog Range and the Mersey are intimately intertwined. The line of peaks is tulampanga, and the Mersey tulaminakili. The spiritual significance of this place is immense. It’s the richest source of ochre in Tasmania. In pre-colonial times, this sacred commodity mined here was traded far and wide.

A second, smaller canyon penetrates the mountains further east, between Magog and Gardners Ridge. Here, the Lobster Rivulet flows, meeting the Mersey on the other side of the range. In the shadowy heart of the canyon is Lobster Falls.

. . .

Lobster Falls was our objective one sunny January morning. Just past Needles, an inconspicuous blue sign marks the start of Lobster Falls Track. From the road, it heads north-west uphill through thick forest, before descending towards the Lobster Rivulet. Upon meeting the rivulet, the track veers northward following the stream. As we progress, the valley sides become steeper. Sweat trickles down my neck as the day heats up. We find a shady spot and stop for a drink. Then we leave the rivulet and begin a long climb over a steep spur. Unseen, we hear water cascading over rocks far below.

It’s fitting Lobster Rivulet bears this name. This is where settlers first came in contact with this iconic animal. But the wildness of the region meant this encounter had to wait more than 20 years after Lieutenant Colonel William Patterson first set up camp near the mouth of the Tamar in 1804.

Giant freshwater crayfish (Astacopsis gouldi) occur in all river catchments emptying into Bass Strait, except the Tamar. About 12,000 years ago, at the end of the last ice age, sea levels began to rise. For centuries, each high tide surged further up the Tamar. Seawater now penetrates more than 50 km inland, rendering the whole valley unsuitable for freshwater lobsters.

In the years following Rolland’s expedition, settlement spread west from Launceston up the Meander Valley. In the spring of 1825, Thomas Cookson Simpson sent men further west to “take up” the first stock run in the Chudleigh Valley. When they drove their cattle through Needles Gap onto the marshy plains, little did they know they were entering lobster country.

Simpson’s overseer, William Knight, and his assigned servant, John Hurling, built their hut and stockyards by the rivulet, halfway between Needles and Chudleigh. Although they’ve been given no formal credit, it’s most likely Knight and Hurling named it “Lobster Rivulet”.

I imagine Knight and Hurling in an idle moment, throwing a line into the stream running past their hut, hoping to catch a fish for their supper. Then I hear their shouting and feel the excitement as they pull in that first lobster.

As well as lobster country, the Chudleigh Valley is pallittorre country. After wintering on the coast, the pallittorre returned to the valley in December 1825. Instead of kangaroo and emu, they found cattle and white men. Conflict soon followed. There were sporadic clashes throughout 1826, mostly involving David Gibson’s men on nearby Dairy Plains. Knight and Hurling lived in a state of constant anxiety, carrying loaded muskets at all times. They felt their isolation keenly.

In January 1827, 20 pallittorre men approached Simpson’s Hut. But Knight and Hurling warned them off without shots being fired. In May, while out hunting kangaroo, Knight was confronted by three pallittorre. He fired at them and brought home as trophies the spears they’d thrown.

On the morning of Saturday June 23, 1827, the misty valley rang with axe blows, as Knight and Hurling felled a large tree near their hut. Unbeknown to the stockkeepers, they were being watched. A pallittorre war party lay hidden in scrub near the rivulet, patiently waiting for their moment. After the tree crashed to the ground, Knight and Hurling retired to the hut for “dinner”. Later, they emerged to lop the branches from the fallen trunk. The warriors saw their chance. The stockkeepers had left their muskets behind. When the pallittorre broke cover, Knight and Hurling realised their fatal mistake and made for the hut. But they’d been outwitted and outflanked. Knight took a spear in the shoulder “thrown by a tall black native”. The stockkeepers turned and ran for the forest on the rise. Knight pulled out the spear but couldn’t keep up with Hurling. Three pallittorre fell upon Knight with waddies, knocking him to the ground. The rest pursued the fleet-footed Hurling towards the tree line.

When the fastest man got within “ten or fifteen yards” of Hurling, he turned and flung his axe. The others slowed to help their injured companion and Hurling made good his escape. Once in the forest, he concealed himself under a fallen log. From his hiding place, Hurling watched the hunters search fruitlessly, before giving up and returning to loot the hut.

Half an hour later, Hurling was discovered, not by the pallittorre, but by his dog. Fearing the dog was followed, he emerged from under the log and ran three kilometres through thick forest over the hill to the safety of Gibson’s Hut. Hurling must have made a curious sight as he burst through the door, the dog at his side, breathless, pale and wearing just a shirt. He’d discarded his boots and trousers, as they’d been slowing him down.

An armed party accompanied Hurling back to Simpson’s Hut. Hurling couldn’t face seeing the mangled body of his good mate Bill. So, the others performed the solemn duty of carrying Knight back to the hut and burying him near the threshold.

The next day, two soldiers of the 40th regiment, Corporal John Shiners and Private James Lingan, field police constable Thomas Williams and two stockkeepers, Thomas Baker and William White, set out from Gibson’s Hut seeking revenge. In the afternoon, they spotted campfire smoke at Caveside, near what they referred to as Laycock’s Falls, now Westmorland Falls.

Before dusk, the men approached as close as they dared, then hid and waited. Under the cover of darkness, they crept silently towards the pallittorre camp. There were six fires, up to 60 people and many dogs. On Corporal Shiners’ signal they opened fire.

The number of Aborigines who died that night is unknown. In the morning, Shiners found blood trails but no bodies. This wasn’t unusual. The pallittorre always “carried the dead men with them”. A newspaper trumpeted that Shiners’ party killed nearly 30 , but also admitted “this is not a positive fact”.

Two centuries later, untangling the truth is impossible. What’s clear is that William Knight’s death and the “Laycock’s Falls Massacre” were not isolated incidents. In June-July 1827, there was open warfare between the pallittorre and the pastoralists, supported by the military and police. Knight was the fourth of six stockkeepers killed and it’s estimated more than 100 pallittorre died in this same period.

It’s time we recognised the Black War as a real war. As real as the Boer War, Vietnam or Afghanistan. Widows silently mourned. Parents wailed. Whole families wept. Whether they did this in a whitewashed cottage or by a campfire surrounded by stringy-bark and myrtle beech doesn’t make their loss any more or less significant. We also need to acknowledge the blood soaked into our own soil, not that of some foreign battlefield. To reap the benefits of what has grown here since – we need to remember and show due respect.

. . .

When the track reaches Lobster Falls, we look down on a series of tranquil pools, linked by small cascades. The final descent isn’t for the faint-hearted. It ends with a nerve-racking traverse of a sloping rock platform, slippery with water trickling from the cliff face. At the bottom, we reward ourselves with lunch and then work our way up the falls to the top pool.

It’s the height of summer and the flow is low. We easily step across where the water gushes from the pool, sparkling and tinkling down to the next level. Basking skinks scatter in all directions as we approach. The cool clear water reflects the brilliant blue sky. In moments like this, joy and peacefulness infuse my soul.

Lobsters were here before Knight and Hurling built their hut a few kilometres upstream. Lobsters were here even before the pallittorre. With any luck, there will still be lobsters here long after we’re gone.

Dr Terry Mulhern is a biochemist, university educator and researcher. If he isn’t in his office or somewhere taking a class, look for him in the basement of the University of Melbourne’s Baillieu Library under 994.6 History, Tasmania. He was the 2018 winner of the David White Award for Teaching Excellence, the University of Melbourne’s highest honour for teaching in Health, Science, Agriculture and Veterinary Science. Terry Mulhern was born in north Queensland and has worked at universities in the UK and around Australia, but his heart is in north-west Tasmania.